Combined harvesters (combines to you and me) have been around as long as the reaper, with Hiram Moore building the first successful one in 1834 in Michigan. It didn’t catch on due to Michigan weather, but when shipped to dry and sunny California in 1854, it performed well.

Pulled by thirty or more horses or mules, these big “prairie” ground-driven combines came into general use in the West and Northern Plains, but were believed to be impractical in the Central and Eastern U.S.

During the second decade of the twentieth century, several manufacturers began experimenting with smaller, lighter combines, mostly with 14- or 16-foot heaters and toothed cylinders and concaves and straw walkers like those used in stationary threshers.

Too big

Even these machines were too large, too expensive, and too heavy for the two- or three-plow tractors of most midwestern and eastern farmers, who farmed a quarter-section or less.

As E.J. Baker put it in a 1960 Reflections column in Implement & Tractor magazine that discussed Harry Merritt and Allis-Chalmers: “Then the combine came over the Rockies into Kansas and later into the Corn Belt. Those three-plow tractors just did not have the stuff to handle those 16-foot Case and Red River Special combines, but the Allis-Chalmers 20-36 waltzed right along with them. Harry profited, and smirked mayhap a bit.”

Harry Merritt and A-C were instrumental in bringing the small combine to U.S. farmers; as Mr. Baker goes on to explain in his inimitable style: “Then, out of the West came Guy Hall, promoter extraordinary, with R.G. Fleming’s wire brush combine, which a three-plow tractor such as the A-C Model U could pull and drive through its power-take-off without strain.

“Guy invited the Reflector up to a Lake County, Illinois, farm, to see how the Fleming-Hall combine worked. Harry Merritt went down from West Allis to see it the same morning.

“The little machine (it was so small it looked ridiculous) was doing a steady, non-plugging job cutting a 5-foot swath of good wheat.

“After watching the outfit a spell, I got down on my knees and searched a cut swath for 5 feet., picking up the reel-shelled and thrown-over kernels. This evidence was given to Harry to figure out roughly the machine’s efficiency. There were astonishingly few kernels for an experimental machine.

“Harry made his deal with Hall and Fleming (Shop rights for $25,000. S.M.) and turned the combine over to Walter Dray for development.” (Dray was at the time working with threshers at the Rumely works, which A-C had just acquired.)

Baker goes on: “He (Dray) had little worry about the All-Crop, as it soon was called, in small-grain or forage seeds, but he was not satisfied with the machine, or any other, in soybeans. Too many cracks and splits.

“He became convinced the wire brush was not as good as Harry Merritt thought it was. Since the wire brush was basically patentable, Harry tended to nurture it, as it were, to his bosom.

“Finally, Walter worked out the rubber-faced bar cylinder (John Mainland, the old thresher designer had told him about carpet-faced beater bars occasionally used in Scotland) and Walter built a hybrid cylinder, one-half wire brush and one-half rubber-faced beater bar. The work of the latter was so much better that Harry reluctantly gave up the wire brush idea.

“Walter’s job was finished, and the All-Crop was turned over to Charlie Scranton, chief engineer at the La Porte Works, to smooth into a production job. How well he did is history, and in a couple of years, the Allis-Chalmers share of the combine trade made Harry Merritt chuckle.”

More of the story

That concludes the comments by Mr. Baker, but not the story. First announced to the public in 1931, the A-C machine was said to permit “anyone who could drive a tractor to cut and thresh their small grains, clovers, peas and beans alone with no more effort than it took to disk those fields.”

Corn Belt combines

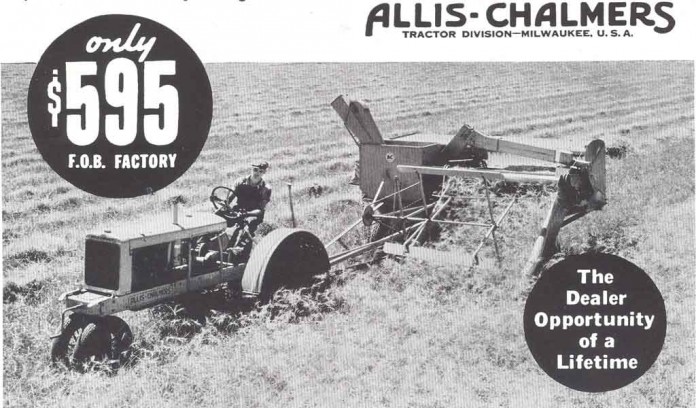

These first “Corn Belt” combines used the wire brush cylinder and 25 were built and tested in 1931, revealing problems with the brush. After Walt Dray and Charlie Scranton were done, the redesigned rub-bar cylinder machine, now called the Model 60 ALL-CROP Harvester, used V-belt drive instead of chain and sprockets, weighed just 2,800 pounds on its rubber tires and was capable of cutting 10 to 20 acres per day.

It had a 5-foot cutter bar, and could successfully “harvest a diversity of seeds — from birdseed to beans.”

That first year of 1935 A-C sold 550 of the machines and more than 7,000 in 1936, at a cost of just $595. Long-time A-C employee, Walt Buescher wrote,

“At the outset the combine was intentionally built flimsy light. Merritt figured that field experimental work would turn up the weak spots. When they were encountered, those areas were beefed up. At the end of the engineering work, and before the introduction of the machine, Merritt had the strongest possible machine with the least possible weight. Steel sells by the pound, so he had a price advantage over the competition.”

Continual improvements

The Model 60 ALL-CROP was made from 1935 through 1952, when it was replaced by the Model 66. Continual improvements were made over the years and the A-C machine remained extremely popular — during several years in the late ’30s it captured more than half of the small combine market, and by the time production ceased in 1952, nearly 252,000 Model 60s had been built.

When I was a kid after World War II, I rode and sacked on an Allis-Chalmers Model 60, a McCormick-Deering No. 42, and a Case Model A-6. I’m not qualified to rate one over the other, but I do remember that when the wind was wrong, the A-C bagging platform got a lot of dirt and chaff from the straw discharge chute that was right beside it.