“But if the house looked prettier at night, why goodness — the sugar house was the prettiest place in the whole world.”

—Marly in the book “Miracles on Maple Hill” by Virginia Sorensen.

JOHNSTOWN, Pa. — A few weeks ago, I wrote about Hurry Hill Maple Farm and Museum, which highlights this award-winning book. In the story, Marly, a 10-year-old girl, travels with her family to their deceased grandmother’s house on Maple Hill in Edinboro, Pennsylvania.

The family hopes that the countryside will ease their dad’s PTSD from war. Almost instantly, Marly becomes fascinated by the sugar house, the woods and the countryside around it.

When reading this story, it dawned on me: I have traveled down a similar road before. In fact, my life didn’t feel so entirely different from Marly’s — the childlike wonder and magic she feels while visiting the sugarhouse.

Like Marly, I remember the first time I laid eyes on my grandfather’s sugarhouse: It felt like falling in love. Perhaps with the woods or maple syrup but mostly I think I fell in love with being a Partsch. This is where my pap and his five brothers spent years making syrup, cooking kielbasa and sharing laughs — this is part of my history.

I never got to see my pap in that sugarhouse — he died when I was 6 years old — but every time I visit it, I feel closer to him.

There was nothing he loved more than his family and his farm. He would collect acorns in the woods and bury them around the property; he planted thousands of trees during his lifetime, a portion of which is former strip mine land. To him, the farm and the woods behind it were his paradise. How could I view it any differently?

Every time I visit the farm, I get the same feeling of butterflies I’ve gotten since I was a little girl. But back then, I wasn’t the one behind the steering wheel, gliding the car up and down the rolling hills of Johnstown, Pennsylvania.

I was the one sitting in the backseat of my dad’s car, holding my breath, waiting for the moment when we crested Beech Hill that would descend down to Grandma’s. When we arrived, the first thing I wanted to do was visit the old sugar camp in the woods. I would beg my dad to take me back there and share stories of making maple syrup.

As I grew older, this fascination has never left me; if anything, the sugar camp reminds me of the type of person I want to be: a steward of the land like Pap.

The sugar house has been home to outdoor critters instead of maple syrup making for years now. One day, we hope to restore it to its former glory. But for now, it sits in the woods, bearing the blunt force of mother nature, waiting for its story to be told — today is that day.

The Partsch sugar camp

Making maple syrup was a family affair from the Partschs’ first batch to their last. My great-grandfather began making maple syrup in the ‘60s on a cast iron kettle that was boiled outside on a wood fire. Before they used metal taps, my Uncle Don and great-grandpap carved taps from sumac wood found on the farm.

My pap followed in his father’s footsteps and built a small sugar house in the woods of the Partsch farm in the ‘70s. He tapped a few trees and made maple syrup on his own for several years before his brothers Vick, Ed, Al, Ray, Harold and his brother-in-law Merle wanted to join in.

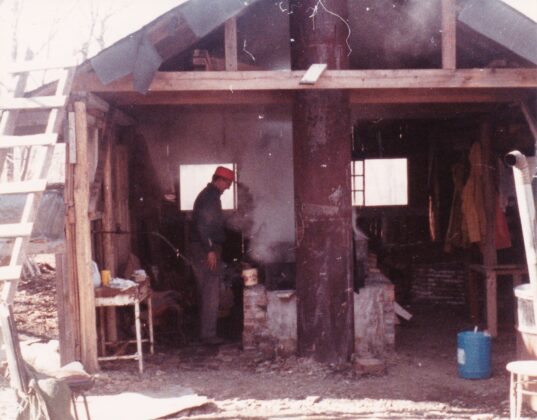

The six brothers built the current-standing maple house in the early ‘80s, out of scrap wood, American chestnut trees, doors, metal siding and shingles to resemble three walls for weathering the elements.

In the sugarhouse was an oven built out of bricks they found at a nearby abandoned coal mine. The bricks were cemented together with fire clay also found at the mine. Attached to the oven was a smoke stack made out of steel water heaters.

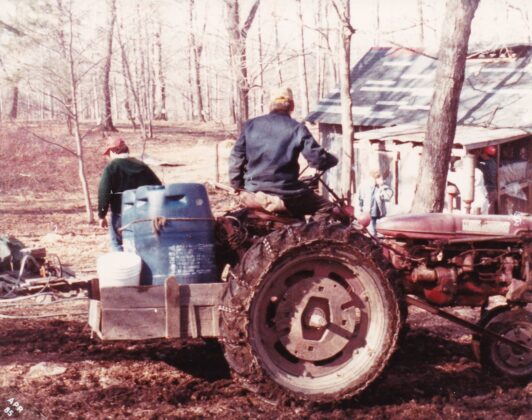

The brothers tapped roughly 300 maple trees scattered across 70 acres of rolling hills. My dad, the brothers, my dad’s sisters and brother and his cousins would collect the sap in plastic milk jugs and dump it into a large barrel that sat on my pap’s tractor and my Uncle Ray’s three-wheeler.

Years later, the brothers would install a tubing system in parts of the woods where the maple trees were close together. Despite this, most of the sap still had to be collected by hand and, according to my dad, “imagine carrying full buckets up a snow-covered hill,” especially if the sap was flowing and you had to do it several times a day.

Once the sap was transported from the woods, it was dumped into a stainless steel holding tank, just outside the sugar house, that the brothers bought from a nearby dairy farm. The sap was pumped into a smaller holding tank inside the sugar house that poured the sap into a large evaporator pan that sat on the edge of the brick oven.

Wood burned inside the oven on railroad crates that would heat up the sap for several hours. If it got too hot while boiling, there were flaps on the roof they could open to let in air.

When the sap moved to the finishing pan, the brothers would take it inside their houses and finish the sap off, filtering it three times over. The brothers then divided up the maple syrup and used it as they wished.

More than anything, the sugar house was home to family gatherings and good food. The Partschs would cook kielbasa and hot dogs, and eat them on benches and a couch that sat in the sugarhouse. Sometimes, they would bake potatoes in the embers of the brick oven and heat up raw sap for maple tea.

My dad spent quite a few weekend nights with his cousins, sleeping on the floor of the sugarhouse, stoking the fire, making sure the sap didn’t burn. By morning, my pap and his brothers took over, trading shifts for sleep in a warm bed.

No one knows for sure when this tradition stopped, but as my dad and his cousins went off to college, operations dwindled as the help left. Today, my dad, his friend Terry Tischler and I are making a small batch of maple syrup using the same metal and plastic taps my great grandpap used decades before.

As my dad and I filter sap on our back porch, the smell of freshly made maple syrup wafts through the air. I smile; the scent transporting me back to the sugar camp in the woods, reminding me of the miracles born on Beech Hill by my pap and his father before him.

(Liz Partsch can be reached at epartsch@farmanddairy.com or 330-337-3419.)

View this post on Instagram