The supply problem

At its core, the issue is about supply and demand. Right now, the market says farmers are producing more milk than is being exported or consumed domestically. That’s according to Dianne Shoemaker, a field specialist in dairy production economics with Ohio State University Extension. Shoemaker knows dairy.1 She’s been with OSU Extension for more than 30 years. She also lives what she teaches. She owns a 150-head dairy farm, in Mahoning County, Ohio, with her husband.

Too much milk and not enough demand for that milk equals low prices. Milk production was up to 218 billion pounds in 2018 nationally, a 1% increase over 2017, according to the annual Milk Production Report released by the USDA-National Agricultural Statistics Service in March 2019.2 Overall, national milk production has increased 15% in the past decade, the data shows. According to the most recent milk production report, production in 2019 was just ahead of 2018.

So, why can’t someone just tell farmers to produce less milk? Canada has a production control system for its dairy industry. Should we adopt something like that? That has its own issues we don’t have time to discuss here. And the U.S. tried its own version of production control in the 1980s (see: Dairy Production Stabilization Act of 1983). It didn’t work long term.

Shoemaker said one of the problems is that farmers have to make decisions at the farm level. They’re not thinking about the world around them and all the mechanisms at play. They are thinking about the things they can control. One of them is how many cows they milk. When prices are low, farmers milk more cows to have more milk to sell. When prices are high, they do the same to make up for what was lost when things were bad. So the answer has always been … milk more cows, no matter what? Yes, you read that right.

“It’s a vicious cycle,” Shoemaker said.

On top of that, milk production tends to increase every year on a per cow basis, thanks to improvements in genetics and management. If farmers did not increase herd size to make more milk, they’d be making more milk anyway.

And, in general, the average dairy farm size is increasing. In Ohio, there were 68 dairy farms with 500 or more cows, according to the 2012 USDA-NASS Census of Agriculture. Five years later, Ohio had 75 farms with 500 or more cows. There was even one farm with 5,000 or more cows. Shoemaker said 30 years ago, a farm could support three families milking 150 cows. Now, a typical farm would need to milk 300-500 cows to support that many people.

The demand problem

It’s true that people aren’t drinking as much milk as they used to. There are a couple of things people point to as the cause. One is that there are a lot of beverage options now.

The National Milk Producers Federation is focused especially on plant-based dairy alternatives — think: almond milk. The federation is fighting against allowing these products to use terms like “milk” and “cheese” in the labeling, arguing that it’s misleading and confusing to consumers. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration took public comment on the issue in early 2019, but hasn’t pursued any action yet.

The sale of plant-based milk alternatives and other dairy alternatives continues to grow each year, according to data compiled for the Plant Based Foods Association.3

Others point to changes in the National School Lunch Program under the Obama administration as the culprit. The Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010 took away flavored milks unless they were fat-free. The low-fat versions were brought back in 2019 after the rules were relaxed by the Trump administration. The USDA claimed children weren’t drinking as much milk when limited to fat-free.4

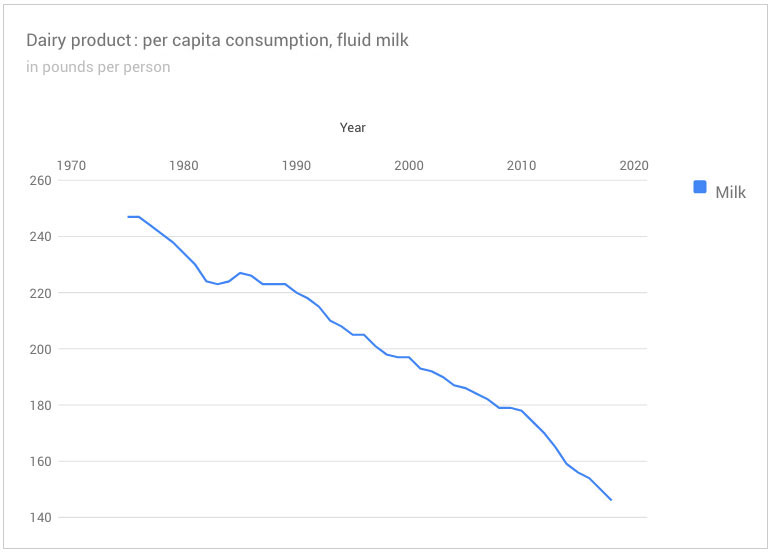

Here’s the thing, though. In the U.S., milk consumption has been on a slow decline for decades. In 1975, people consumed 247 pounds a year per capita, according to USDA-compiled data.5 It was down to 146 pounds per person in 2018.

Dairy consumption in the U.S. is actually up, however. It’s crept up from 539 pounds per person per year in 1975 to 646 pounds per person in 2018, the USDA numbers show. Americans are consuming more yogurt, butter and cheese than they did 40 years ago. Cheese consumption saw tremendous growth, especially non-American varieties.

But it’s butter that’s been the savior of the industry in the past five years, said Peter Vitaliano, chief economist with the National Milk Producers Federation. “If the price of butter had not recovered, dairy farmers would’ve been much worse off,” he said.

During a time when the price of milk has been lackluster, the price of butter has been “quite strong,” Vitaliano said. After years of being told butter was bad for its saturated fat content, research in the last decade walked that back, and consumers reacted quickly. “They like the taste of fat. They were tired of being told it was bad for them. They went back to consuming butter big time,” Vitaliano said.

But butter can’t save the dairy industry alone. Neither can cheese or yogurt, although we’ll talk more about cheese in another story. Maybe people should just drink more milk? It’s not that easy.

The world around us

Dairy products that people don’t consume directly play a lot into the equation. Both at home and abroad. The U.S. is a leading exporter of skim milk powder, whey products and lactose. These things become ingredients in other food products and animal feed.

“The world market has a huge impact on what’s going on in dairy farms all over the United States,” Vitaliano said.

Exports of dairy products grew from just under $1.6 billion in 2004 to nearly $6.8 billion in 2014, according to a USDA-Economic Research Service, or ERS, report from November 2016.6 During this time, the U.S. became the world’s third-largest dairy product exporter, behind New Zealand and the European Union.

The rapid growth happened for a bunch of different reasons, the report stated. Income growth in Asia and Latin American led to increased dairy consumption. Market-based reforms in China made it a big dairy importer. Free trade agreements and reduced domestic support for dairy products launched the U.S. into world markets.

The value of U.S. dairy exports fell in 2015, for a bunch of other reasons: global dairy demand slowed, milk supply quotas were discontinued in the European Union and the U.S. dollar strengthened, among other things, according to the report. Things haven’t really picked up, Vitaliano said.

“It’s critical we get exports growing again,” he said.

Exports might be the answer to lagging milk consumption, or at least part of it. When milk production outpaced demand domestically, exporting dairy products helped fix that problem for a while. When exports slowed down, milk prices slumped.

“What happens half a world away can hit hard on the farm,” Vitaliano said.

Problems at home

So that touches on supply, demand, the entire world … but what’s going on at home?

Farmers are feeding their cows, milking their cows and trying to make ends meet. It’s been tough to do that when milk prices are lower than the costs of producing that milk. Feed costs are the most important part of a dairy farmer’s budget. The margin between the price received for milk and the price paid for feed is what makes or breaks a farm.

Years ago, farmers didn’t have to pay close attention to the margins because feed prices were low and relatively stable, Vitaliano said. Corn was about $2 a bushel and soybeans were $5 a bushel. Then, the price of grain became volatile, “driven by ethanol mandates and a big export demand for U.S. grain,” he said.

The price of corn surged in 2006, going up about a dollar in a year to about $3 per bushel, according to ERS data. Prices continued upward until about 2012, when farmers were getting paid about nearly $7 per bushel. The higher cost of feed didn’t impact small farmers as much. Those farmers tended to grow their own feed, so they actually benefited some when the price of corn increased.

“The milk price went up enough to cover the higher cost of feed. If you were producing your own feed, you got an extra boost in your margins,” Vitaliano said.

When feed costs came down — it’s about $4 per bushel for corn now — so did the milk price. Farms that were buying feed breathed a sigh of relief. But smaller farms got squeezed, Vitaliano said.

“Small farmers that were marketing grain through their cows, they weren’t making money on that either. Milk prices stayed low. They were squeezed in two places,” he said.

The times they are a-changin’

In the past, Vitaliano said farmers could usually count on every third year being a good one. They could weather a couple bad years, but the third one would come along and things would turn around.

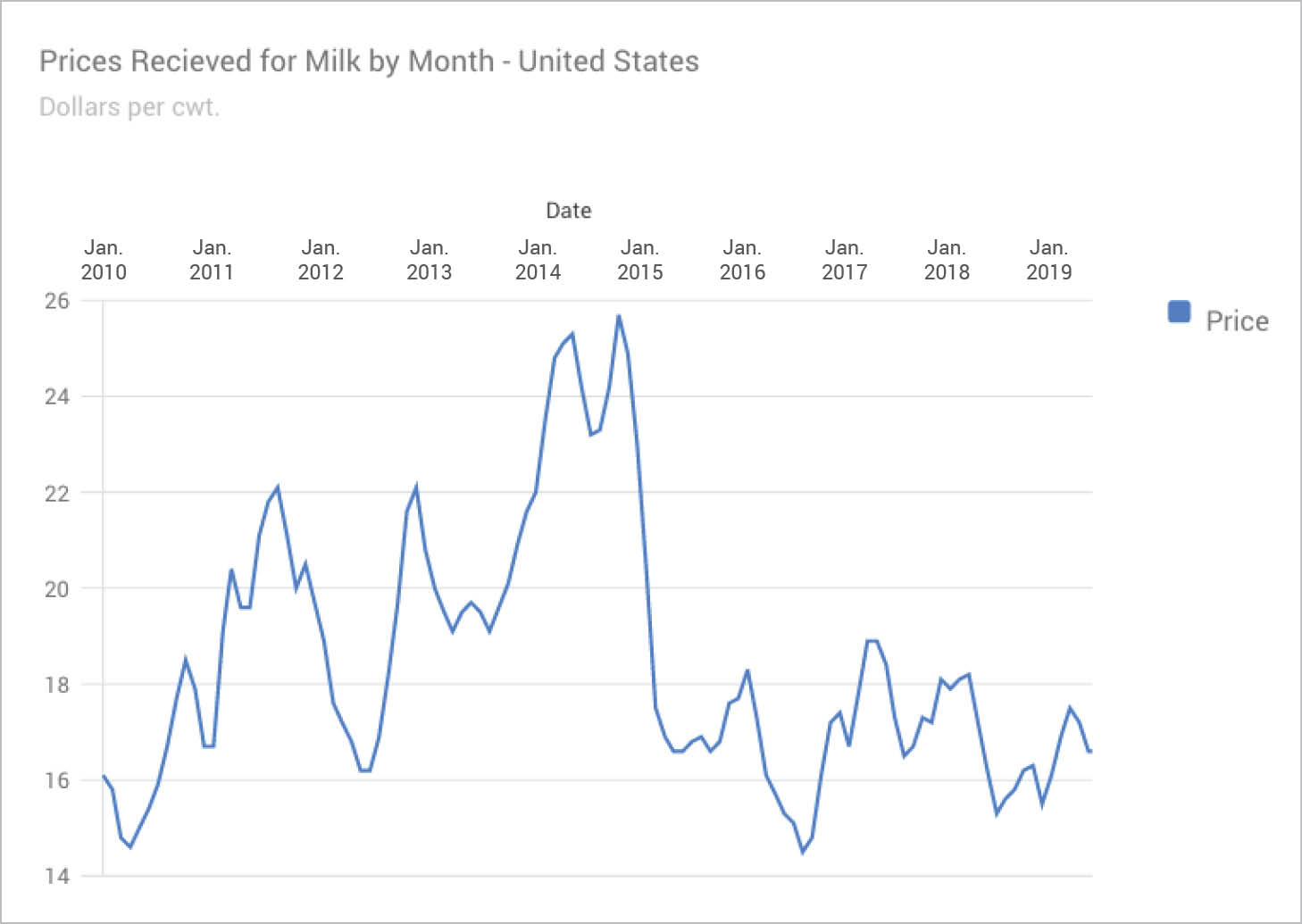

Now it’s been nearly five years of low milk prices. It started in 2015. The statistical uniform price per hundredweight dropped from $19.74 in December 2014 to $16.67 in January 2015, according to Mideast Marketing Area Federal Order 33 statistics.7 That’s about 15% in 30 days. The lowest lows came in 2016. The price hovered around $14 for the first half of the year, hitting a low of $13.81 per hundredweight in May.

Things weren’t much better in 2017 and 2018. Farmers who were relying on that third year to be better are being stretched thin, and some are being forced to call it quits. Shoemaker wrote in her October Dairy Excel column in Farm and Dairy that 262 Ohio dairy farms ceased milk production from October 2018 to October 2019.8 That’s 80 more farms than the year before.

Things began looking up early this year, though. Milk prices began improving in March. The November statistical uniform price was $18.01 per hundredweight. That’s $2.33 higher than the price in November 2018. But for a lot of farmers, it’s too little, too late.

“The farms that had higher costs of production are still struggling to meet cash flow obligations,” Shoemaker said. “If they’re still milking, the challenge is ‘how do I adjust so I can better survive the next downturn and recover from this one.’”

In a business that is powerfully impacted by things that are out of their control, what are dairy farmers to do to steer their own destinies? They can milk more cows. We talked about that already. It’s problematic for the industry as a whole, but it can be the answer for the individual farmer. They can also control milk components, or how much milk fat and protein is in the milk. That’s the single biggest way a farm can impact its milk price, Shoemaker said. Farmers are paid more for higher percentages of milk fat and protein.

Some farms rely on diversification, whether that’s also running a grain business, using some of their milk to make cheese or raising other livestock. We’ll talk more about some of those farmers in coming weeks. Otherwise, it’s all about management, Shoemaker said. Managing production, finances, people, cows and land.

“Not thinking of it as a business has gotten a lot of people in trouble,” Shoemaker said.

Shoemaker said that was a fundamental shift that happened in the 1980s. People used to think of farming as just a way of life. Now, it needs to be more like “farming as a business so you can have it as a way of life,” she said. To be sustainable, a farm has to first be profitable.

“You have to be making money to do things the way we want to do them, to conserve those natural resources,” Shoemaker said.

(Reporter Rachel Wagoner can be contacted at 800-837-3419 or rachel@farmanddairy.com.)

Sources:

- Farm or nonfarm worlds: Extension dairy specialist knows both sides

- Milk Production Report

- Plant-Based Foods Association sales data

- Child Nutrition Programs: Flexibilities for Milk, Whole Grains, and Sodium Requirements

- Dairy consumption data

- Growth of U.S. Dairy Exports

- Federal Milk Marketing Order 33 Statistical Uniform Price

- Farm exits likely to continue

Boring. Same old story with no insight as to solution. Two comments. 1)If there is an oversupply of milk the simple solution is to produce less. . U make a brief passing remark about Canada and though certainly not a perfect syste; It works.

2) you mention milk alternatives and their inroads on the beverage shelves—-does the industry fight back? The milk alternatives spend millions demonizing milk; the industry says little. The big milk players proudly proclaim that they plan to participate by distributing their own milk alternatives. Great response. If you cant beat them join them.

Milk is still the most near perfect food available. It’s been advancing humankind for more than 10 000 years; the Bible speaks of the “land of milk and honey” more than two dozen times. Most criticisms of milk are anecdotal and change with the seasons. Either milk is deserving of our praise or not—-,not perfect but far more perfect than any of the alternatives. I could go on but would hope you will. There is no oversupply–,that IS NOT THE PROBLEM- the problem is that we choose not to defend this precious food and fail miserably in our efforts distinguish ourselves from the grossly overpriced alternatives. I beg unto do. Better

Amen, well said!!

The dairy products prices in the grocery store NEVER go down, the money is there to pay the producers more, the. creamery associations and giant soulless conglomerates are simply expecting the people who are in the trenches for them to endlessly bleed and do the suffering then be happy when their despotic overlords throw them a bone.

Unfortunately farmers will never get organized and say “No you want this product you will pay what we need to survive”. So the American farmer continues endure death by a thousand cuts.

Why no discussion of distorting subsidies, fed & state, to expand? Real issue is gov’t interference in marketplace which rewards expansion/greed. Example: $750k COVID payment to big unit, while small farm may be paid $10k. Many, many , many subsidies for the bigs

Small units can compete on a fair playing field, but gov’t tilts it to favor size. Sad taxpayer is supporting this transformation.