SALEM, Ohio — Bill Wickerham has had issues with the black vultures on his farm in Adams County for over 10 years now, but it wasn’t until last year that he experienced his first loss due to a vulture attack.

A set of newborn twin calves were the target of the attack. A group of black vultures, catching the scent of fresh birth, approached the mother cow and her calves from the side. “They attack in numbers and go for the soft fleshy parts (of the newborn calves),” said Wickerham.

“A good cow will actually run them out,” he said. But when the cow ran the vultures out from one side, another group of vultures was waiting to converge from the other.

Wickerham raises around 50 brood cows on his roughly 200-acre cow-calf operation just outside of West Union, Ohio. Wickerham said he has dealt with some near misses, but had never lost a calf due to a vulture attack until last summer. “It is a very frustrating thing to have to deal with,” he said.

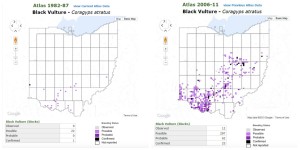

Historically, southwest Ohio has been hot spot for black vulture sightings and threats, but the birds seem to be on the move, with reports coming in as far north as Summit County this year.

About black vultures

Ohio livestock producers have been dealing with increasing threats of black vultures over the past 15 years, explained Ohio State Extension Program Assistant Stan Smith, of Fairfield County, in an Ohio Beef Cattle newsletter.

Black vultures and turkey vultures are often seen together, even roosting in large dead trees together, but are actually different species. Turkey vultures are often recognized by their red heads, while black vultures have black heads and are smaller in size. Black vultures also have white tips on the underside of their wings which can be seen in flight.

Black vultures are aggressive and attack live animals for food, while the turkey vulture prefers to feed on the carcasses of already dead animals. Black vultures are known to prey on livestock in labor, sometimes attacking while the newborn animal is still in the birth canal, Smith said.

Increased damages

“Undoubtedly, the black vulture seems to cause the most damage — whether it’s predation in young livestock or structural damage,” said Jeff Pelc, Ohio district supervisor, USDA/APHIS, Wildlife Services.

Damages reported so far in 2016 (January-Sept. 30) totaled $44,500 for both livestock and property (structures, boats, vehicles, etc.). Of that total, $29,077 was reported in livestock losses. This is up from the 2015 report where black vulture livestock damages were reported at $4,056 and total damages were $4,556.

The reports are compiled from technical assistant requests received by the USDA-Wildlife Service. Producers can report damages/losses in a technical assistance call or request a specialist to come out and assess the damage. Pelc said last year Wildlife Services received seven technical assistance calls with livestock damages and have received 19 so far this year. He said they are not sure at this point if the increase in calls correlates with an increase in birds or if it’s just an increase in awareness.

Related: Black vulture kills increasing in Ohio

Where are they

In general, black vulture predation has been reported in southwest Ohio, with many reports coming from Adams, Brown and Highland counties, Pelc said. Reports have also come in from central Ohio (Fairfield and Licking counties) and more recently in eastern Ohio (Coshocton, Muskingum, Guernsey and Belmont counties). A report also came in from Summit County this year.

The top five counties with technical assistance requests for black vulture threats or damage to livestock in 2016 were Carroll, Clermont, Fayette, Highland and Muskingum, said Pelc.

Pelc said it is unclear whether the vultures are expanding their range, but it is clear that the vultures tend to stick around Ohio during the winter, due to the availability of food and shelter. Turkey vultures, on the other hand, are more likely to head for warmer climates, said Pelc.

Protecting your farm

Vultures are protected under the Migratory Bird Treaty of 1918. This means it is illegal to capture or kill the birds without a Migratory Bird Depredation Permit. Livestock producers are, however, allowed to harass the birds without obtaining a permit. Pelc encourages using harassment methods before applying for a permit.

Harassment methods include letting a dog out to scare the birds, using pyrotechnics, shooting near the birds (without actually shooting the birds), and making any loud noises. Pelc also said it is important to clean up any dead carcasses — as the rotting smell attracts the birds — and remove any dead trees in the pasture area, as this is a preferred place for them to roost.

Depredation permits

If all else fails, a producer can apply for a permit that allows them to shoot a few birds a year, explained Pelc. In Ohio, the first year a livestock producer applies for a permit — due to experiences with predation or threats (from the vultures) — the permit is free, said Pelc. In subsequent years, the permit is $100.

The producer does not have to have predation or threats from the vultures to apply for a permit and in some cases a permit can be issued the same day. Each permit is issued on a case-by-case basis. The amount of birds a producer is allowed to kill is assigned to them depending on their situation.

“It’s typically 3 to 5 vultures,” said Pelc. “If the producer gets his limit and is still having problems, we can get that permit amended.” Producers are encouraged to shoot one or two birds to use as an effigy, by hanging the dead bird by its feet near an area where the birds roost or surrounding a livestock area.

“They are very social birds and responsive to that negative sight of seeing one of their flock members die,” said Pelc. Producers are required to continue to use harassment techniques even after obtaining a permit to limit the number of birds killed.

Harass them

“One thing I have shared with others is to consider a rotational grazing setup,” said Wickerham. “When a cow gets ready to calve, she typically moves away from the herd. That’s when they are most susceptible,” he said.

In a rotational grazing setup, it is harder for the cow to get away from the rest of the herd, being confined to a smaller area of pasture. Wickerham said when his calves were attacked, the cattle had been moved to a paddock where they had a little more room to spread out, and the cow was able to get away from the rest of the herd.

“I came home in the middle of the day and had calves with vultures circling,” he said.

Wickerham had applied for a permit, but by the time the permit came he had successfully scared the birds off and never used it. In most cases, he has been able to harass the birds away by shooting a gun or finding other ways to make loud noises until the birds left.