As Americans, we love a story about the good immigrants — the ones who came here “the right way.” The ones who came here with the right papers through the right process, became citizens and began working their way up the ladder, pulling themselves up by their bootstraps. All to earn their little slice of the American dream.

It’s what most of our ancestors did. I know it’s what my father’s family did, emigrating from Hungary in the early 20th century.

Time buried the reason why my great-great grandparents came here, but it’s safe to assume it was the same reason many people still immigrate here. To make a good living. To take care of their families. To leave turmoil and violence behind. To be safe. I don’t think anyone uproots their entire life for no reason.

The story of my ancestors, and probably yours too, is not so different from the stories of today’s undocumented immigrants, except that today’s immigrants are more likely to be brown and Latino than white and European. They’re the invisible force that powers the agricultural sector in Ohio.

The difference is that coming here legally — and being able to be the good immigrant — is much more difficult now, if not damn near impossible. The risks undocumented immigrants take to work and live in Ohio are immense.

For decades there has been no clear way to get legal status or citizenship if a person was considered to be undocumented, and there was little hope for one to be created. Most recently, the Trump administration cracked down on immigration of all kinds.

That changed Jan. 20. On the first day of his presidency, Joe Biden unveiled a sweeping immigration reform bill to Congress that included a pathway to citizenship for undocumented immigrants, and, with it, came a sliver of hope.

• • •

There are more than half a million immigrants, or foreign-born individuals, living in Ohio. About 100,000 undocumented immigrants live in Ohio, according to New American Economy, a bipartisan immigration research and advocacy organization. Undocumented immigrants are defined as foreign-born individuals without authorization to be in the U.S.

Not all undocumented immigrants come from Mexico or other Latin American countries and not all work in agriculture, but many do.

About 25% of Ohio’s undocumented population was born in Mexico, Pew Research found. The second largest country of birth was India, making up 13% of the undocumented population. The third was Guatemala, with 9%.

What is an undocumented immigrant?

A foreign-born person who does not possess a valid visa or other immigration documentation. This could be because they entered the U.S. without inspection or overstayed a temporary visa.

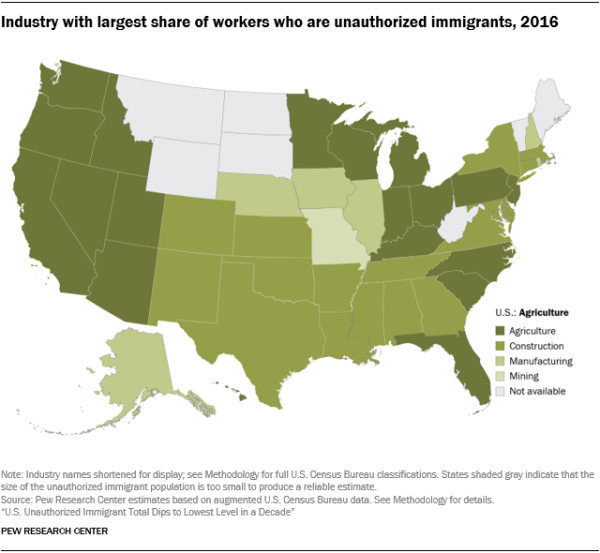

And it is agriculture that uses the largest percentage of workers who are undocumented immigrants, reports Pew. Data gathered by the American Immigration Council shows that immigrants make up about 11% of all workers in agriculture in Ohio.

These numbers don’t include migrant farm workers, many of whom are undocumented, who come to Ohio to work for a season before moving on to another state for different work.

This is all to say that immigrants, especially those without authorization to be here, are critical to Ohio’s agricultural sector. They’re doing jobs that farms need — that American-born workers won’t do.

A 2014 study commissioned by American Farm Bureau Federation found that the majority of Americans “believe that they have ‘outgrown’ farm work as reflected in their unwillingness to take farm jobs even temporarily despite being unemployed.”

“While the generally low wages to paid farmworkers are consistent with the low-skill nature of the work, far more Americans are willing to accept even lower minimum wage jobs rather than work in agriculture,” explained the report, titled “Gauging the Farm Sector’s Sensitivity to Immigration Reform via Changes in Labor Costs and Availability.”

• • •

Immigration issues might seem more relevant in other parts of the country, like California, Florida or Texas, but they hit much closer to home than many people realize.

The 2006 Annual Report of the Ohio Migrant Agricultural Ombudsman noted that three major cucumber growers would not be growing cucumbers for pickling in 2007 because of concerns about Immigration and Customs Enforcement and lack of immigration reform.

“They have been operating with some level of assurance that they will not be prosecuted, but with the possibility of new personnel each agricultural season comes the risk of new employees not having their own legitimate documentation,” the report reads. “It is common knowledge that the majority of migrant farm workers are undocumented.”

In June 2018, immigration agents conducted three raids in Ohio and arrested 260 people, mostly Mexican and Guatemalan immigrants. Two raids were at gardening and landscaping centers in Sandusky and Castalia. One was at the Fresh Mark meatpacking plant in Salem, where 146 people were arrested. The raids split up families and left some children without parents. People lost their jobs.

In Salem, a handful of people ended up being deported, but the experience left a lasting impact on the families and the community, according to a report from the Center for Law and Social Policy, released in July 2020. The national nonprofit visited Salem and Sandusky 18 months after the raids and interviewed impacted immigrants as well as legal service providers, community organizers, social workers and government officials.

A community-based provider noted in the report that many of the Guatemalan workers in the Salem raid had already undergone “significant trauma in their home country and during their journey to the United States, with several pursuing asylum.”

“A mother in Ohio wept as she recalled being jailed and having heartbreaking phone calls with her 4-year-old daughter who would constantly beg her to come home,” the report stated.

• • •

Why don’t people just come here legally?

It’s a question Silvia Hernandez is used to hearing. She is executive director at Starting Point Outreach Center, a Christian nonprofit in Willard, Ohio, that serves as a resource to connect residents with services, assistance or whatever it is they might need. The town is about 15% Hispanic, and that number swells to about 20% when migrant farmworkers return for the summer.

Willard is home to Buurma Farms, Weirs Farms and Holthouse Farms, major vegetable growers that sell their produce to national retailers. Much of their workforce during the growing season is Latino immigrants.

After the ICE raid in Sandusky, which is about 30 miles away from Willard, people asked her why those workers never applied for citizenship.

“It’s so incredibly difficult,” she’d explain. “There is no pathway.”

Hernandez, 26, knows personally how impossible it is. She’s undocumented.

Her family moved to Willard from Mexico when she was 4. The small agricultural town in north central Ohio reminded her mother of the countryside where she grew up. Her family was trying to get away from crime and violence in the city. They immigrated to the U.S. for safety, Hernandez said, but they didn’t have an asylum case.

Her parents found jobs. Hernandez went to school at Willard City Schools. They went to church. They were, for all intents and purposes, a normal American family, except for one thing.

“I always say I was raised by this community,” Hernandez said. “What makes me different than my neighbor is that I don’t have a Social Security number.”

That never mattered to Hernandez growing up. It didn’t hit her until high school that her options were limited by her lack of legal status.

“When I was a senior in high school, when friends were thinking about college, it hit me that I was raised here and I knew everybody, but they didn’t know that I had no social security number,” she said. “I couldn’t apply for a driver’s license. It hit me like a ton of bricks. ‘What am I going to do?’”

It was around this time in 2012 that former President Barack Obama created the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program. When Hernandez first applied for DACA, Starting Point helped find her resources to guide her through the process.

It’s not legal status, but it does prevent her from being deported and allows her to apply for a driver’s license and work permit. She has to renew her status every two years.

In her first job after becoming a DACA recipient, Hernandez worked in a vegetable packing house. It’s the industry her mother has worked in since the family moved to Ohio.

She later got a job working at an insurance agency. She went to college while she worked, but had to pay out of pocket because she wasn’t eligible for federal financial aid because she’s undocumented. Eventually the money ran out and she had to put her college dreams on hold.

• • •

The story of my family’s arrival in the U.S. may sound familiar. It might feel a lot like your family’s origin story. They came over on a boat and went through the port of entry in Baltimore.

Gyorgy and Rosa Farkas and their teenage son, Lajos, emigrated from Hungary in 1913. Lajos later became Louis Farkas. He married another Hungarian immigrant, Rose Biro. They had 11 children, one of whom was my grandfather, Louis Jr.

The couple moved around the Ohio River Valley before eventually settling down in Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania. Louis Sr. found steady work at Babcock and Wilcox Steel. He was an ordinary guy. Another cog in the American industrial machine.

Hungarian was the language spoken at home, although they’d lived in the U.S. for decades. It’s the first language their children learned. The story goes that my grandpap, who was born in the U.S., had difficulty when he started grade school because he didn’t speak English.

Louis Sr. became a naturalized citizen in 1922, nine years after he set foot in the U.S. The process to become a citizen then was fairly simple. First, you file a “Declaration of Intention.” You didn’t have to do this right away, but most people did it within the first couple years they were in the country.

In the declaration, Louis Sr. swore that he wasn’t an anarchist or polygamist. He had to announce his “bona fide intention to renounce forever all allegiance and fidelity to any foreign prince, potentate, state or sovereignty.”

Then, after a few years, you could petition the court to become a citizen. At the time, a person had to live in the U.S. for at least five years and have the two people swear that they “possess a good moral character.” Then, a judge would have a hearing to approve or deny the petition.

There was no visa system at this time. That came later. For the most part, you showed up at a port of entry, and they let you in.

Only about 1% of 25 million immigrants from Europe who arrived at Ellis island between 1880 and World War I were denied entry, according to the American Immigration Council.

The first restriction on immigration was the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. It stopped Chinese workers from entering the U.S., because of race-driven fears that they were stealing Americans’ jobs.

The Immigration Act of 1882 put a head tax on each immigrant and denied entry to “any convict, lunatic, idiot or any person unable to take care of himself or herself without becoming a public charge.” In 1917, a literacy test was put in place for incoming immigrants.

The Quota Law of 1921 and Immigration Act of 1924 created the first numerical limits on immigration based on race and nationality, favoring western European immigrants. It set up the visa system and established the Border Patrol.

Restricting immigration based on who is desirable and undesirable isn’t new. Neither are immigrants entering the country without authorization. The Immigration Service reported 1.4 million immigrants living in the country illegally in 1925.

• • •

There are four main ways to immigrate to the U.S: family, employment, humanitarian and the diversity visa lottery. All of them have restrictions.

“This system wasn’t set up for people to get here legally,” said Eugenio Mollo, an attorney with Advocates for Basic Legal Equality. ABLE is a nonprofit law firm based in Ohio that serves low income individuals. Mollo works specifically in immigration and farmworker issues.

The system is also set up to make daily life difficult for people without legal immigration status. Immigrants without legal status can’t get a driver’s license in Ohio, although they can in 15 other states, including Pennsylvania. They can’t get insurance. They don’t have Social Security numbers.

In northern Ohio, dealing with Border Patrol and immigration agents is a concern. There is a Border Patrol station in Port Clinton, in Sandusky County.

“Border Patrol presence is a factor that many migrant farmworker families take into consideration in deciding whether to come to Ohio or not,” Mollo said.

When undocumented immigrants drive around, they’re taking a lot of risks. But how does a person get around rural Ohio without a car? Arturo Ortiz, a paralegal with ABLE that handles immigration and farmworker issues, said they don’t want to break the law, but it’s unavoidable.

“They’re not criminals,” Ortiz said. “They just want to work to feed their families.”

• • •

Silvia Hernandez works voluntarily as an ombudsman for a local vegetable farm that has many immigrant workers. She’s the liaison between the employer and the workers.

“My name and number is printed on every check,” she said. “Employees can call me with any questions, concerns. I’m available any day of the week. Sometimes people work ‘til 10 or 11 p.m., then they had a question.”

She reports feedback to the heads of the company. Then they work out a solution. Sometimes it involves a conference call with her, the worker and the boss.

“We’ve had a lot of small issues resolved this way,” she said.

Not all immigrant workers are so lucky. Undocumented workers are more vulnerable to abuse and exploitation in their jobs, Ortiz said. They often receive lower wages than workers with legal status or U.S. citizens.

“They’re at the mercy of their employer,” Ortiz said. “If you complain about conditions, you’ll get fired.”

Immigrants without legal status are not eligible for any federal benefits, but many do pay taxes on their income. While some undocumented workers seek out jobs that pay under the table, many get a taxpayer identification number that can be used instead of a Social Security number to take taxes out of their paychecks.

Undocumented immigrants paid an estimated $178.5 million in federal taxes and $117.7 million in state and local taxes in Ohio in 2019, according to New American Economy.

• • •

Biden’s plan would create a path for certain undocumented immigrants to earn legal status and citizenship. The U.S. Citizenship Act would allow people to apply for temporary legal status, with the ability to apply for green cards after five years if they pass background checks and pay their taxes. Three years after that, green card holders can apply to become citizens.

DACA recipients, farmworkers and those with temporary protected status who meet certain requirements could be eligible for a green card, immediately.

The bill would also reduce family visa backlogs, eliminate the three- and 10-year bars on family petitions and provide new funding for English-language instruction.

Some Republican lawmakers are decrying the plan. U.S. Sen. Tom Cotton, of Arkansas, tweeted Jan. 18 that the bill was “total amnesty” with “no regard for the health or security of Americans and zero enforcement.”

Giving undocumented immigrants a path to citizenship isn’t a new concept. Most recently, the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986, or IRCA, allowed nearly 2.7 million people to gain legal status.

“Legalization has profound, positive economic effects for its beneficiaries,” according to a policy brief put together in January 2014, by the Migration Policy Institute. “Wages of those legalized increased by as much as 15% within five years and 20% over the long run, while educational attainment, occupational status and homeownership markedly increased, and poverty rates declined.”

National farm groups, like National Farmers Union and the United Fresh Produce Association, are encouraged by the proposed immigration reform. The United Farm Workers, a California-based union supporting farmworkers, called the bill “fundamentally different than what any other president has ever done in emancipating farm workers.”

Ortiz said he got calls from clients before the inauguration asking if the Biden presidency would mean a pathway to legal status. Mollo called Biden’s proposal a “reasoned framework” that “lays out the guideposts of smart and necessary immigration reform.”

It’s up to Congress to enact meaningful change, though, Mollo said. The president can’t do it on his own. Democrats have razor-thin majorities in the House and Senate, and some Republicans are resistant to Biden’s plan. The immigration bill will have a steep hill to climb.

Hernandez said she’s hopeful for the future and anxious to see what happens next with Biden’s proposal.

“It’s very positive for a lot of people who have been waiting and are on this cycle,” she said. “I call it the hamster wheel. We’re not really sure what’s going to happen next. I’m hopeful that a good result will come out of the new administration.”

(Reporter Rachel Wagoner can be contacted at 800-837-3419 or rachel@farmanddairy.com.)

What a poor excuse of journalism. Farm and Dairy should be ashamed to publish this one sided article that is long on opinion and short on facts. The Biden administration is no friend of agriculture.

I believe in immigration. Most all of us, unless Native American, have immigrant ancestry. And the process to gain lawful entry, whether for citizenship or work visa, should be easier. That being said, The Biden plan to “open the gates” is destructive at best. Perhaps Ms Wagoner should write a story based on the trauma of American citizens who have been robbed, beaten, raped, or killed by unlawful immigrants, some being multiple offenders. Or let’s see a story about the drug addicts (two deaths in 7 days here in our small town) and the expense and trauma that they cause friends and family. And the dealers? Waiting to come across the border. Not to mention that my (our) hard earned dollars will feed and house them, plus give them free healthcare that I pay dearly for. I’m with Joe…..

Hi John, I’d love to chat with you about this more. You can reach me on my cell at 724-201-1544.

Also, Farm and Dairy has covered drug addiction issues in small towns. The staff did an extensive series titled Rural Addiction in 2017. You can find all the stories at http://www.farmanddairy.com/ruraladdiction. Let us know what you think.

Well done Rachel, and spot on…thank you

As someone from a rural area, I know firsthand how much farms rely on immigrant labor, and it’s refreshing to see that finally being acknowledged in policy conversations. Biden’s immigration proposal might feel like a D.C. issue to some, but for Ohio farmers, it’s directly tied to whether crops get planted, picked, and processed on time.

What stood out to me was how the article explained that many farmworkers are undocumented, but have been doing this hard, essential work for years—often decades. They’re not just temporary hands; they’re the backbone of the ag industry, and without a pathway to legal status, both workers and farmers are stuck in limbo.

I also appreciated the focus on stability. The article made it clear that creating a more reliable, fair immigration system would benefit everyone—from laborers to consumers. Less uncertainty means better planning, better yields, and, frankly, better food on our tables.

This isn’t about politics—it’s about people and practical solutions. If you care about local farms, food supply, or the economy in general, this article is worth a read. It really connects the dots.