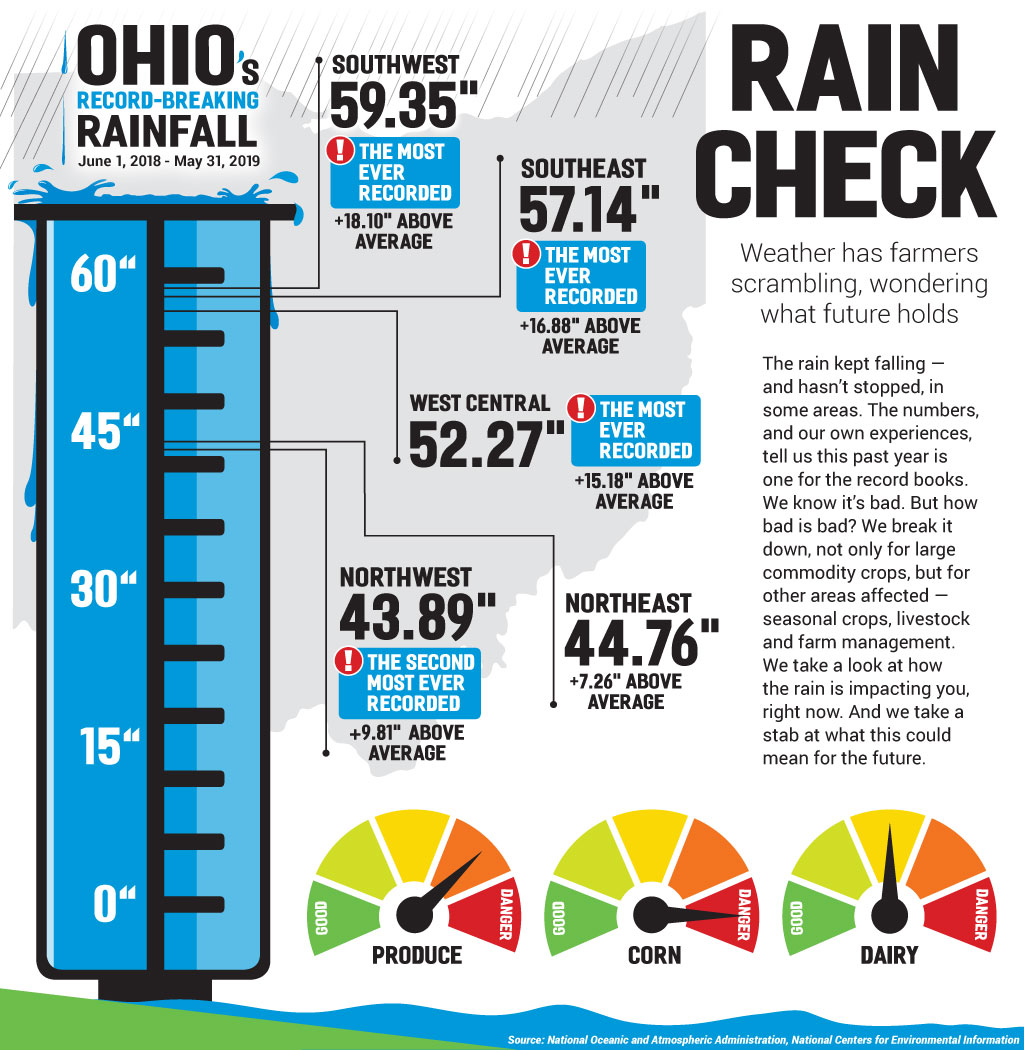

The rain kept falling — and hasn’t stopped, in some areas. The numbers, and our own experiences, tell us this past year is one for the record books. We know it’s bad. But how bad is bad? We break it down, not only for large commodity crops, but for other areas affected — seasonal crops, livestock and farm management.

We take a look at how the rain is impacting you, right now. And we take a stab at what this could mean for the future.

Rain hampers bees

The rain is even impacting some of the smallest agricultural workers: the bees.

When it rains, bees don’t fly, thus reducing their working time, said George Stacey, president of the Columbiana and Mahoning County Beekeepers Association.

Ralph Rupert, vice president of the group, said this has delayed pollination by a couple of weeks.

Even when bees have been able to get out of the hive, the rain has diluted the pollen and nectar, the beekeepers said.

Stacey said all of these things could impact the quantity of honey beekeepers are able to harvest.

Bees bring in nectar to make honey to supply the hive, and “they’re going to supply the hive first,” he said.

There’s also been more swarm activity, and it’s happening later than usual. Swarming is when a large group of bees leave an established colony to create a new colony and cluster on a stationary object.

They didn’t see swarms in May, but they are seeing them into July, which is unusual.

“Later swarms won’t be able to build up the hive and get food to survive the winter without substituting sugar syrup for them,” Stacey said.

During this past winter, an estimated 37% of managed honey bee colonies in the U.S. were lost, according to a survey of 47,000 beekeepers. The survey was conducted by the Bee Informed Partnership.

These losses were 9% above the average of winter losses since the annual survey began in 2006.

Fruit, produce in trouble

It’s not just the spring weather that affected fruit and produce growers, but the winter as well. Rain, cooler temperatures and limited pollination are all playing a part in what is expected to be a stunted harvest.

John Huffman, of Huffman Fruit Farm in Salem, Ohio, and Jeanne Woolf, of Woolf Farms in East Rochester, Ohio, both only have about a third of a peach crop due to saturation and winter injury. Their strawberries have also struggled with the saturation.

David Hull, of White House Fruit Farms in Canfield, Ohio, said farmers face increased costs associated with preventing disease in crops. Saturation increases disease risks, even on farms that take precautions.

“I think it’s impacting everybody,” said Steve Hirzel, president of Hirzel Canning Co., in Northwood, Ohio. The company, which markets the Dei Fratelli line of products, works with 30 growers. This spring has been hard on them.

“Everything got extremely delayed,” Hirzel said. “The planting window was much tighter. We expect it’s going to condense our production, too.”

Huffman said the long-term effects are hard to predict. The lower peach yield will hurt the farms’ incomes. His blueberries, raspberries and blackberries are doing well. With good conditions, struggling crops may recover.

“There’s a lot of hope yet,” he said. “It could still be a good season for what we grow.”

For Hirzel, the long-term impacts are yet to be felt. He expects a shorter picking time, and said the delayed growing season will run into the fall’s first frost. He expects it will impact the amount of holdover inventory his company will have for 2020.

But those impacts will also affect the growers.

“For the grower, it’s serious,” Hirzel said. “That’s their livelihood.”

Corn, soybeans disastrous

Mark Drewes, of Custar, Ohio, was still trying to plant 1,600 acres of corn in late June. He needs it to feed his cows.

After losing his alfalfa production to winter kill, Drewes has few options.

Drewes took prevented planting on several thousand acres and is only planting soybeans on acres where landlords have a share in the crop and do not have crop insurance.

Peter Thomison, an Ohio State University Extension agronomist, said late-planted corn will be more susceptible to dry conditions, disease, especially if the harvest season is wet, and frost damage.

Laura Lindsey, state specialist for soybean and small grains, said prolonged saturation in fields can kill soybeans that have already been planted.

Drewes said unplanted acres may cause water quality issues. Without crops to retain nutrients, the nutrients in the soil will wash away.

Seed from fall 2018 was not high quality because of weather conditions last year, and Lindsey said if farmers choose to hold seed from 2018 until 2020, the quality could become a serious concern.

Thomison predicted low yields and more corn used as silage due to low quality. Lower quality and fewer planted acres means less corn will be available to sell this fall.

“The local supply system is at great peril,” Drewes said. “This is not a little flesh wound … it’s a deep wound with a lot of scars.”

Hay, forage critical

It wasn’t just the spring rain that hammered forage stands in Ohio, it was the rain that fell last fall, and then freeze-thaw cycles during the winter.

The result: Up to 80% of stands — specifically alfalfa stands — in certain areas of the Midwest were completely destroyed.

And if your stands survived, first cutting of that hay was next to impossible, and if you were able to take it off, overall yield was lower than normal and its nutritional quality was also lower because of grass and other weeds in the stands.

Ray Wells, a Ross County beef cattleman, said June 25 was the first day they were able to mow hay this year.

“It’s way overripe and mature. There’s a lot of weeds,” he said. “It’s a mess.”

Those who were able to get in sooner may face later problems from harvesting on saturated soil, which can do long-term compaction damage and lower the productivity of future crops, said Stan Smith, an Ohio State University Extension program assistant in agriculture and natural resources.

The hay inventory in Ohio has dipped to the fourth lowest level in the 70 years of reporting inventory.

It’s a scenario years in the making, Smith said. Many acres were converted into corn and soybeans when prices were high in 2010-2012, and has not been converted back, despite the increase in cattle numbers as markets have strengthened.

According to U.S. Department of Agriculture records, Ohio’s farmers had roughly 410,000 tons of hay on hand in May 2017.

In May 2019, hay levels were at 180,000 tons.

“There’s very little stored hay in the Midwest, and there’s been very little opportunity to harvest more,” Smith said. “It’s a huge challenge.”

Dairy under pressure

Dairy farmers came into this rainy year in an already unstable environment, and over the last 18 months, a considerable number of farmers have sold their herds.

The weather, now combined with the market forces, has some people questioning “Am I going to stay in it?”

“No doubt we’re going to have fewer farms in Ohio and across the U.S.,” said Dr. Maurice Eastridge, Ohio State University Extension dairy specialist.

The weather — with its huge impact on milk producers’ manure, crop and forage situations — “just really puts into play that farmers continue to live on the edge,” he added.

“It’s going to be a tight year, relative to supply and needs on the farm.”

We don’t know all the long-term ramifications, but if it continues to be wet, stressful year, there’s a risk for mycotoxins in forage harvested later this year and fed into the next year that could impact production and health of the animals, even into next year.

Farmers also need to their long-term plans for: 1) manure storage to handle volatility of the weather and crop condition; and 2) feed storage to deal with volatility in crop production.

“I think it’s not as doom and gloom for Ohio,” Eastridge said, “but it all depends on the farm.”

Cattle, sheep feeling effects of weather

Beef cattle and sheep farmers have fared better than some, but are still dealing with last year’s issues and looking ahead to more.

Ray Wells, a Ross County cattleman, said his cows were in poor condition coming out of winter after fall calving because of last year’s hay quality and extreme fluctuations in weather. They were either knee deep in mud or stumbling over the hard, unevenly frozen ground.

John Anderson, a sheep farmer in Wayne County, said the rain and cool weather has promoted the growth of cool season grasses, making plentiful forages. The problem is keeping up with it, especially if low-lying pastures are too wet to put animals on.

Once grass goes to head, it’s harder for ruminants to digest, although cattle seem to fare better than sheep, Anderson said.

“It makes for really long days,” he said. “You don’t get very much time to breathe.”

Anderson said flies tend to be an issue when things stay wet, but the cool weather also seems to have kept them at bay. Kathy Bielek, another Wayne County sheep farmer, said the same for parasites, with the long pasture growth keeping the sheep grazing above the worm larvae.

Both shepherds said things could go south fast as the summer heats up.

Looming hay shortages and increased prices for corn and soybeans could also impact cattle and sheep farmers who feed grain-mix rations.

Wheat harvest slow

In late June, John Hoffman, of Circleville, Ohio, had just pulled out of a wheat field because of rain. He still had 60 acres to harvest.

“The rains really started in July of last year,” he said in an interview after he’d gotten rained out. “We’re getting rain all the time.”

He said it would take two days to get back into the field. And, by then, he expected sprouting. Test weights were also likely to drop.

Hoffman farms 3,000 acres in Pickaway County, with 300 in wheat.

He normally has a yield of 100 bushels per acre. He expected a 10-15% decrease this year.

The quality was decent, he said, with no signs of vomitoxin. Any delayed harvest was likely to lead to sprouting though. Hoffman said moisture levels were at 14-16%.

Ohio wheat growers expected to harvest 420,000 acres of wheat this year, down 30,000 acres from 2018, according to the June report of the U.S. Department of Agriculture National Agricultural Statistics Service. Average bushels per acre were down about 12 bushels.

In 2018, winter wheat was 77% good to excellent condition. As of June 2, only 32% made that mark.

Overall, wheat was late maturing, with heading behind the 2018 mark by almost 20%.

Hoffman also farms corn and soybeans, which has been tough. He did take some prevent plant acres.

Looking ahead, he expects he will need to apply a lot of fungicide when the corn tassels. Soybeans were slow growing, without a lot of sunny weather at first.

“It’s a pretty sad state of affairs,” Hoffman said. “The weather is costing me money.”

Not one word about Climate Change- the elephant in the room. If we don’t mention it, maybe it will go away….