Last year, Larry Daugherty had no problem selling 53 whole hogs. He couldn’t keep bacon and other popular meats in stock. It would sell as soon as he got it home from the butcher.

Daugherty runs Heritage Farms, in McClellandtown, Pennsylvania, where he raises heritage breed hogs on pasture to sell directly to consumers. He sells whole hogs and retail cuts.

“We actually had a waiting list for hogs,” he said. This year, he’s sold four whole hogs. Retail sales are down too.

“Normally bacon is our biggest seller,” he said. “We’re sitting on like 30 pounds of bacon. That’s unheard of.”

It’s a similar story for Giana Van Nice, who runs Blue Dog Farms, with her husband, Dan, in New Freedom, Pennsylvania. They produce grassfed and finished beef and pastured poultry and pork. She saw the biggest difference in sales from the height of the pandemic to now in her chicken sales.

“We would butcher chickens. I’d put them in the store at like 2 a.m. and at 5 a.m., they’d be sold out. Like 200 chickens. People would be coming to pick them up and they’d be angry with me that I put maximums on orders,” she said. That was how it went last summer.

The last round of chicken she did this year was the same routine. Butcher about 200 and put them in the store late that night. By the next day, three had sold.

“I have seven freezers in our basement and they’re filled to the brim with chicken,” she said.

What happened in 2020

The pandemic changed the way people bought and ate their food. At least, for a little bit. At least, for some people.

Restaurants closed. Grocery store shelves sat empty when traditional supply chains broke down. This pushed many people to discover or rediscover local food sources.

Farms and agricultural businesses were deemed essential, and therefore stayed open through the uncertainty at the beginning of the pandemic. Because their supply chains were much shorter and less complex, they were more steady and reliable. Farmers markets saw banner years. Farmers that engage in direct sales reported record sales and interest.

Farm and Dairy wrote about the boost to the buy local food trend, as did many other media outlets. It created optimism within the small farm community. Maybe local food systems wouldn’t just be a niche anymore. Maybe, if the support of these new customers stayed for the long term, small farmers could scale up and become more profitable and competitive.

With the gift of hindsight, it seems like a lot of that optimism was premature.

Consumer spending on groceries did increase more than 60% in mid-March 2020, compared with January 2020, in Pennsylvania and Ohio, according to Tracktherecovery.org, a project of Harvard University that tracks economic recovery of the pandemic.

But while many people did turn to local food sources, most people stuck with the same grocery stores. A lot of those people who turned to local foods in a panic returned to grocery stores once things stabilized.

A national survey of 5,000 people conducted in the fall of 2020 found that big box stores and grocery stores continued to be the most common choice for U.S. consumers to buy food during the first several months of the pandemic.

The Consumer Food Insights survey was born out of a joint project between Colorado State University, Pennsylvania State University’s Northeast Regional Center for Rural Development, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Agricultural Marketing Service and the University of Kentucky looking into the local food system’s response to COVID.

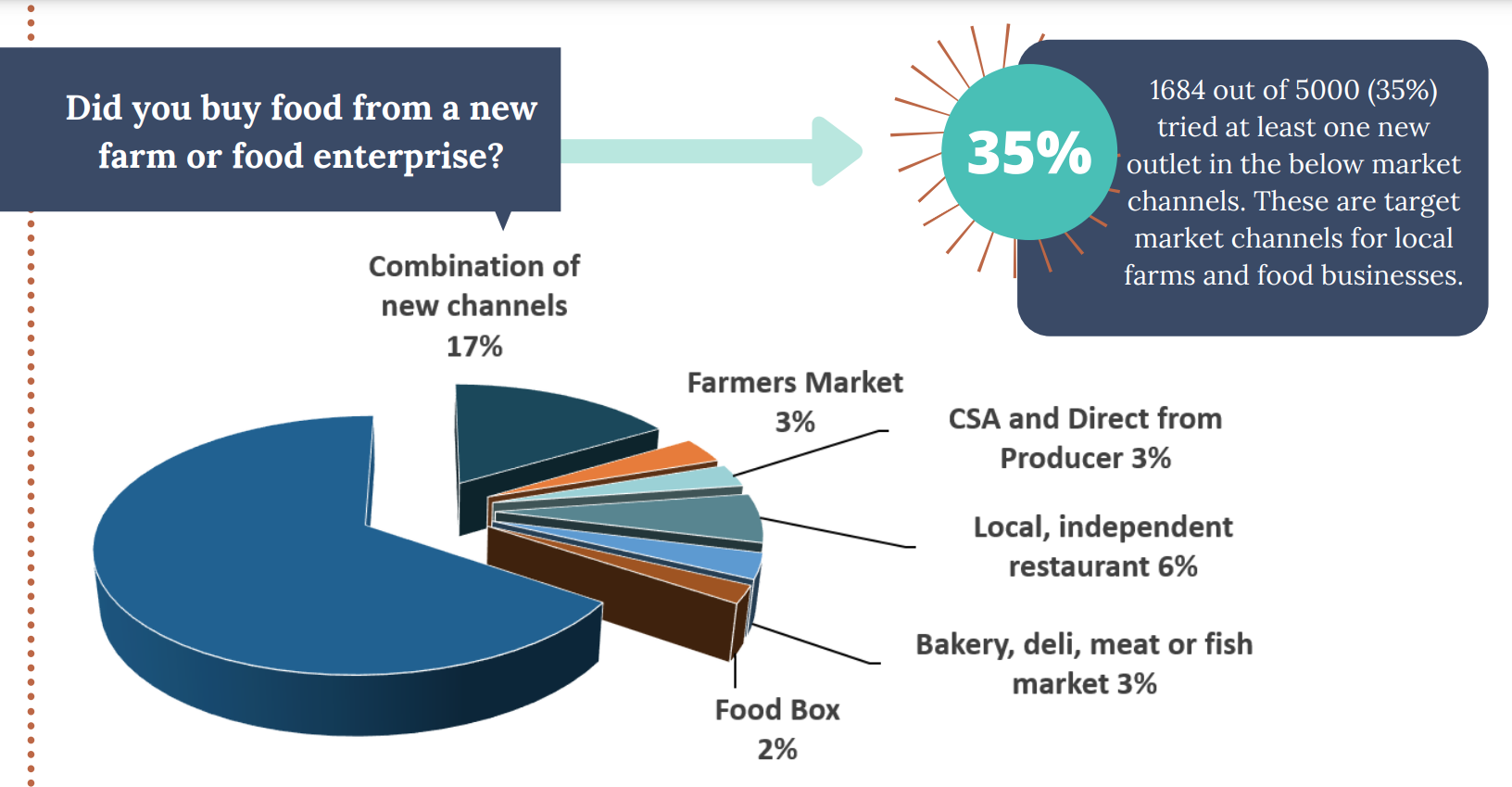

There was a small, but significant switch by some consumers to try new retailers. The survey found that 35% of respondents tried at least one new outlet for buying food, which included farmers markets, CSAs, direct sales farms, local independent restaurants, bakeries, delis or meat markets, food boxes or a combination of new markets. Of the 1,500 respondents that began shopping at local markets, 1,100 were still there in September.

What happened this year

There isn’t hard data available yet for consumer buying trends in 2021, but one can infer from anecdotal data that the number of people buying from local markets dropped off even more in the new year.

Why this happened is hard to say exactly, but economists will tell you consumers are creatures of habit. They like the convenience and familiarity of the grocery store or superstore, where they can buy everything they need at the same time.

“There are lots of pressures [consumers] are facing,” said Zoë Plakias, assistant professor in Ohio State University’s department of agricultural, environmental and development economics. She studies U.S. supply chains and food systems, with a focus on short supply chains, direct marketing and local foods.

Additionally, many local food systems in this part of the world are seasonal in nature, and some people went back into lockdown through the winter months.

“In the winter, we sort of holed up,” Plakias said. “Maybe they lost touch with their local producers over the winter.”

It’s easy to vilify consumers that turned their backs on local foods, but Plakias said we need to consider how different the world is now. In the spring and summer of 2020, people were panicking about how and where to get food when their usual sources let them down. They were also forced to stay home and cook for themselves. That’s not the case this year.

Supply chains stabilized and adapted. At the same time, people are getting vaccinated. They’re traveling and going on vacations. Work, sports and school activities opened again. Life is busy again.

“People weren’t facing the same set of environmental constraints they were in 2020,” she said.

Giving people options

The idea of buying local is still important, though, whether or not consumers act on that belief.

Respondents to the Consumer Food Insights survey said supporting the local economy was the most important factor when people from communities of all sizes considered buying food. People ranked having a locally grown product as the third most important factor in shaping their buying decisions.

The second most important factor: having options on how to buy food. This may point to why places like Yellow House Cheese, in Seville, Ohio, are not seeing a collapse in their new business model.

Kevin and Kristyn Henslee, of Medina County, began by making sheep and cow’s milk cheese and selling it primarily to high-end restaurants, but also selling it locally at farmers markets. They also raise and sell pastured beef, pork, lamb, chicken and Thanksgiving turkeys.

When the pandemic closed restaurants last spring, much of their steady restaurant business dried up with it. At the same time, farmers markets crowds presented a lot of health and safety concerns for the Henslees.

So, they quit farmers markets, went online and brought a bunch of other producers with them. The Henslees found other farmers in the region selling vegetables, fruit, bread, baked goods, maple syrup and mushrooms.

The farmers tell Yellow House Cheese what they have available at the beginning of the week. It gets posted to the online store. People have through Thursday to order. The Henslees send the farmers a list of what sold; farmers drop off their products at the farm Friday. Orders are packed and delivered on Saturday to one of four drop-off locations around the region.

“It’s a way better use of our time,” said Kristyn Henslee, rather than attending farmers markets.

They’re continuing to grow at a slow, but steady pace. Much of the online customer base followed the Henslees over from the farmers markets. There were some slow times this summer, when orders dropped off, but the Henslees recognized that people are going on vacation. Those customers came back.

The Henslees tapped into a few things that consumers like about larger retail stores: online ordering, curbside pick-up and being able to get different types of products all at once.

The Consumer Food Insights survey found online shopping direct from farmers and farmers markets increased from 37%, in September 2019, to 48%, in September 2020. Getting farmers market-type food without having to go to the physical farmers market is part of what keeps his customers ordering, Kevin Henslee said.

“I think the pandemic made it more acceptable to find alternate ways to get food,” he said.

But he is also continuing to see people who are concerned about what the food system looks like, and how things happening thousands of miles away can cause shortages and other impacts, locally. The growth comes largely from customers who want to know where their food comes from and interact with local farmers.

“I think there’s been somewhat of a shift,” Kevin Henslee said. “If you have a local producer, [the food is] here.”

Riding the storm out

An article published in November 2020, by three Michigan State University Extension specialists, predicted that because the buy local movement was growing before COVID-19, it would continue to do so in 2021.

“It would be worthwhile for direct market producers to plan on increased 2021 sales and adjust production and marketing,” reads the article titled, “How food purchasing changed in 2020 — Did we get it right?”

It suggested farmers not doing direct marketing look into it and that livestock producers think about increasing stock numbers to meet the anticipated high demand in 2021.

Van Nice, of York County, Pennsylvania, is glad she did not do that. In fact, after seeing how poorly chicken sales were going, she called the hatchery to cancel three batches of meat chicks she had planned to raise through the rest of the summer.

She can’t, however, cancel the pigs that they’re already raising. Last year, Blue Dog Farms sold out of all 40 hogs it finished instantly, she said. This year, people backed out, even after putting down a nonrefundable deposit. The farm bought a freezer truck to fit all the extra meat it was sitting on.

“I still have pigs going to the butcher in the fall, and I have a freezer truck full of pork,” she said.

Van Nice lost her job at the beginning of the pandemic. It was fortuitous timing, because then she needed to be home to teach her five children and run a booming farm business. Things began slowing down in the winter, as they tend to do with seasonal businesses. But they never picked back up.

“This year, June was my worst month. It was worse than February. And that was a huge wake-up call,” she said.

She was able to find another off-farm job that provided for the family, but that leaves her with less time to be with her children and run the farm. Sales are down this year, even compared with how business was in 2019 before the pandemic.

Van Nice understands what consumers are going through. It’s about riding out this storm and adjusting how they do things next year, just as they rode out the unexpected increase in sales last year

“Every year, we learn and try to change and get better,” she said. “We’re not going anywhere. We’re going to hunker down.”

But she also remembers the conversations she had with new customers in her driveway as they picked up orders last summer.

“I had people say, ‘This is the best thing ever. I’m local for life. I’m never going back. It’s so nice knowing where your food comes from,’” she said

Finding new outlets

Though sales are down for Heritage Farms, in Fayette County, Pennsylvania, this year, it has another outlet for its meat: a food trailer.

The trailer sources all of its meat from the farm. The Daughertys do pulled pork, brisket, rib dinners, meatball subs and chili. Larry Daugherty bought a used enclosed trailer and built everything in it himself for about $2,000. It hit the road in July 2019.

Last year, neighboring Greene County held many events outside with food trucks or trailers. Daugherty said it was a banner year.

This year, with sales down for whole animals and retail cuts, the Daughertys started converting most of their hogs to cuts they can push through the food trailer.

“This entire year, we’ve concentrated on nothing but events, instead of selling halves and wholes,” he said. “That’s the great thing about diversifying. When one thing slacks off, another thing picks up a little bit.”

Silver linings

So, how can small farmers and local food producers keep consumers around without a global pandemic that literally blows up the competition?

First, view 2020 as an anomaly, but don’t throw away the lessons learned, the innovations, the pivots that kept them afloat and helped them thrive. Things like going online, finding a different outlet for products or taking a step back in certain areas when necessary.

“I hope we can learn things from this last year,” Plakias said. “There is such a desire to return to normal. Whatever that looks like. I’m afraid that those cool things, the silver linings of this disaster, will be lost.

“I think this is a good time right now to reflect on what happened, what went well, what is something that we did that was new and we didn’t do for long, because we didn’t have to.”

Second, if you’re wondering where consumers went, Plakias says this might be a good time to just ask them. It’s time to plan for 2022, anyway. If farms switched to any kind of online ordering or purchasing platform last year, they probably have email addresses for customers. That’s something they have over selling strictly at farmers markets to strangers.

Send customers a survey with a few simple questions to find out what challenges they’re facing and how the farmers could address them. Where are they shopping? Where are they spending their time? What do they need from local producers? What would make them come back?

“Focus on consumers and what they want and need,” Plakias said. “I think we all get wrapped up in our own activities. It’s so hard to manage our own lives. Thinking about other people is hard. But to the extent that producers can empathize with consumers and actually do some research … Asking those questions can be super helpful.”

(Reporter Rachel Wagoner can be contacted at 800-837-3419 or rachel@farmanddairy.com.)