Tillage can be part of a holistic soil health management system, according to results from a new study released by a Pennsylvania-based sustainable agriculture group.

Pasa Sustainable Agriculture released the results of a four-year soil health benchmark study March 4. The study collected data from 106 vegetable, row crop and pastured livestock farms in Pennsylvania and Maryland.

“We found that, while most no-till farms participating in our study did indeed have optimal soil health, farms that rely on tillage for controlling weeds and preparing fields were also capable of achieving optimal soil health,” said Franklin Egan, one of the study authors, in a statement. Sarah Bay Nawa was the other author of the study.

Methodology

The study began with a small cohort of a dozen vegetable farms, but grew to include 21 pastured livestock operations, 26 row crop farms and 48 vegetable farms. The farms were a mix of management practices.

The study collected field soil samples and farm management records from participating farms. Tests were run by Cornell Soil Health Laboratory, looking at 13 measures of soil health.

This included: organic matter, soil protein, soil respiration, active carbon, available water capacity, aggregate stability, pH level, phosphorus, potassium and minor elements.

The farms were then ranked overall with optimal being the best soil health and constrained being the worst. The study also looked at three management practices that most influence soil health: days of living cover, tillage intensity and organic inputs.

Tillage

No-till is often touted as the best way to build organic matter and, therefore, soil health, but the study turned this notion on its head.

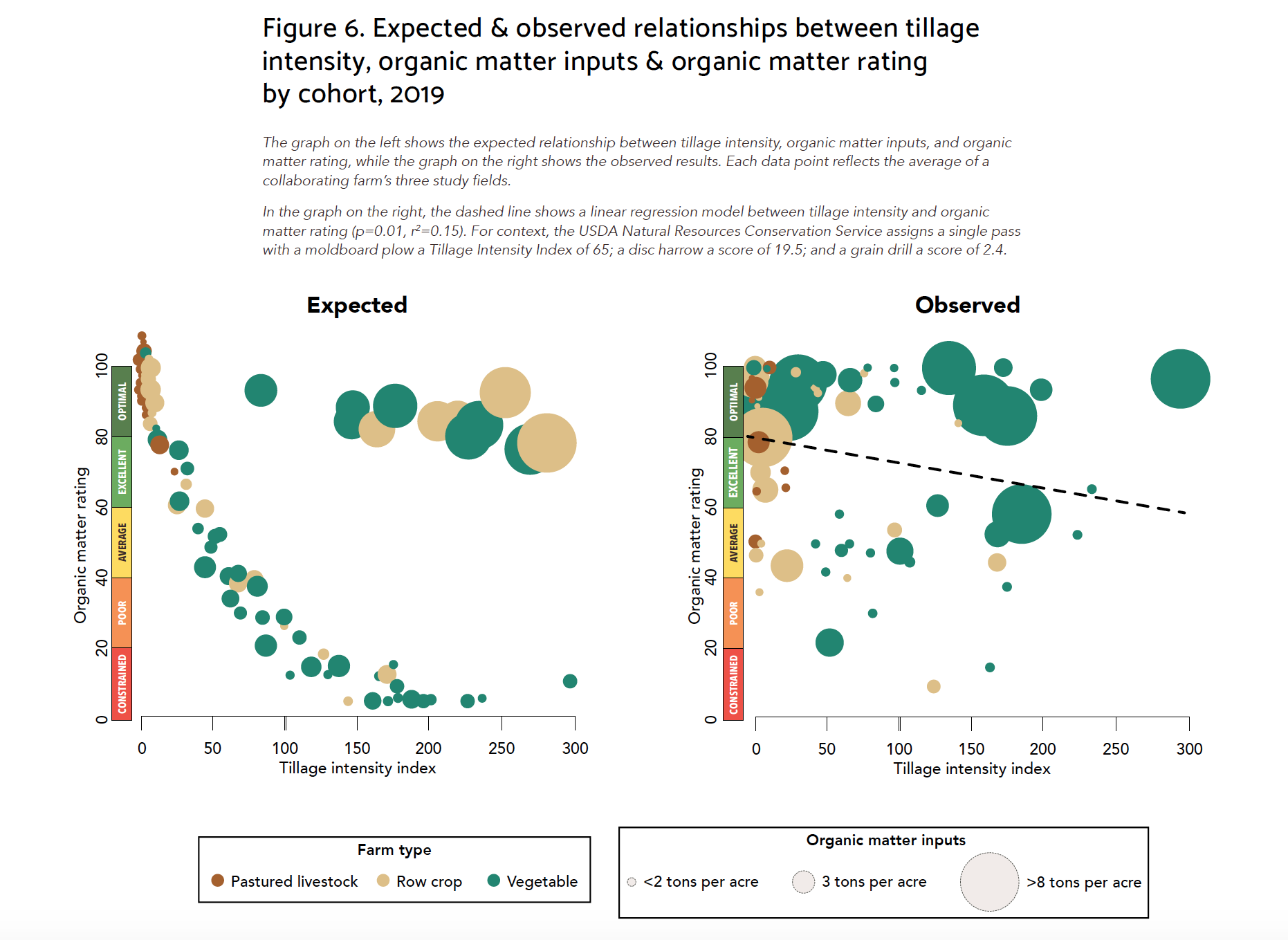

Tilling and cultivating have long been connected with depleted organic matter, and therefore, soil health. The authors expected to find a “steep and consistent negative relationship between tillage intensity and organic matter.” They also expected to find more inputs of manure, compost or mulch to counteract the impacts of the soil disturbance.

The results showed that nine row crop and vegetable farms use tillage and also scored an optimal rating for the level of organic matter, however. These farms also applied relatively small quantities of organic matter inputs to their fields annually.

These findings are important because it could give farmers more options. No-till farmers often use herbicides to control weeds and terminate cover crops. Most organic farms instead use tillage to control weeds.

“These findings point to exciting possibilities for blending the best practices from both no-till and organic systems to help farmers and other stakeholders make more informed decisions about how to best preserve soil health, while also protecting human and ecosystem health,” the report states.

Other results

The study also found that pastured livestock farms outpaced the crop farms in terms of soil health. Many of the vegetable farms and some of the row crop farms had high levels of phosphorus in their soil.

Harsh weather is also tough on soil health, as shown by how the soil dealt with historic rainfalls in 2018. A 60% drop in aggregate stability was observed in row crop farms, during that time. Vegetable farms saw a 54% drop in aggregate stability.

Aggregate stability recovered somewhat the next growing season, fortunately, Egan wrote.

A summary of the study and the entire report can be found on Pasa Sustainable Agriculture’s website at www.pasafarming.org.

(Reporter Rachel Wagoner can be contacted at 800-837-3419 or rachel@farmanddairy.com.)