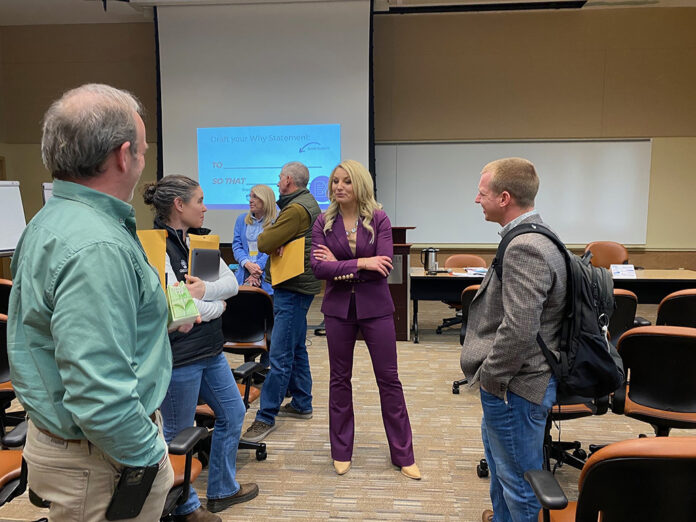

STATE COLLEGE, Pa. — Nearly 400 producers and agribusiness representatives were asked to consider the question “What is your why?” on Feb. 5 at the annual Pennsylvania Dairy Summit at the Penn Stater Hotel and Conference Center in State College.

“Your why can overcome obstacles, inspire action and you can move forward,” said Peggy Coffeen, founder and host of the Uplevel Dairy Podcast, referencing a book called “Start With Why” by Simon Sinek.

Coffeen has been sitting down with dairy farmers from across the country to tell their stories for the past 15 years. She’s noticed as dairies grow, owners and managers struggle to transition from managing cows to managing people and business. As a dairy farmer, you don’t necessarily influence your family and community by what you do or how you do it, but by why you do it, Coffeen said.

Personal experience

Growing up on a dairy farm, Coffee relied on her “why” to overcome obstacles. During her speech, she recalled a time, at 17 years old, when she got stuck in a field called “the wet bottom” driving an Allis-Chalmers 6080 tractor pulling a New Holland box spreader. She asked attendees if they were ever stuck in a rut, feeling in over their heads and spinning their wheels, noting it’s then that we think about why we do what we do.

It’s the love of what you do “that gets you out of bed,” Coffeen said.

The “why” is not money, profitability or family, she said. Instead, it’s the sense of purpose driving your decision-making every day. Loyalty is built on inspiration, not manipulation. In any operation, inspiring others is crucial to success.

It is important to communicate the “why” to family members and employees to ensure the future of the operation and to ease times of family transition and other important events.

“Inspire those around you to take action,” Coffeen said.

Getting family members, employees and the broader community to “buy in to your ‘why,’” she said, will convince others of your value as a farmer.

Defining your “why”

Your “why” is found in purpose and passion, Coffeen said. It is the deep-seated cause or belief that provides passion and inspiration time and time again.

For dairy farms, the underlying “why” conveys the importance of maintaining that passion to move forward. It’s why your farm exists and why anyone should care.

“Few things are as emotional as family farms,” Coffeen said.

The goal brought down through generations at her own family farm, Al-ICKX Holstein Farm in Monticello, Wisconsin, is to “protect a legacy so that future generations can have opportunities to farm,” she said.

Coffeen has encountered many examples of “why” in family farm operations throughout her career. At Brey Family Beef in Door County, Wisconsin, the “why” is “to learn and adapt so that all may have a quality of life.” In Waterville, Iowa, at Rolinda Dairy it’s “to give others an opportunity they may not have otherwise had so that all can be successful.”

Omar Guerrero at Drake Dairy in Elkhart Lake, Wisconsin, said his “why” is “to show his wife the American dream so that others may see what’s possible for themselves.” Jared Dueppengiesser, of Milk Source’s Rosendale Dairy in Fond Du Lac, Wisconsin, said it’s “to leave here better so that others can be successful in their lives at work and at home.”

Passing on a farm in succession planning can be a result of “why,” Coffeen said.

Deep discussions

In the presentation and workshop, “Finding Fairness in Farm Transitions: Is it Fair? Should it be?”, Dr. Brian Reed, a dairy transition and transformation consultant from Manheim, emphasized the importance of having “deep discussions about whatever is fair.”

Rarely, Reed said, is equal fair and vice-versa. “It’s complicated,” he said.

Also, it’s important to utilize strategic planning for a farm transition by identifying where the operation is currently at, where it’s headed and how those in charge are going to get it there, according to Reed.

“Fast-forward 30 to 40 years and figure out what makes sense,” he said.

Does the family have special-needs members? What about long-term care for parents or grandparents? Is there a viable farm business to pass on?

“If you’re not getting along with your sibling, why go into business with them?” he said. “Consider each family member.”

Families should meet with all stakeholders to review the plans, goals, concerns, possibilities and ground rules of the farm business.

“Communication is vital. Facilitation and outside advisers can be very valuable. There are many opportunities for assistance out there,” Reed said. “The final step for many families may be a family meeting led by the senior generation to explain the plan and why it is fair in their eyes.”

Reed’s farm transition presentation included a workshop to discuss a bevy of issues. One group examined a scenario with multiple siblings and two cousins, but its discussion raised more questions than answers.

Each succession should have a take, but the price of farmland continues to skyrocket. In 1997, according to the American Farm Bureau, the average price per acre of land in the U.S. was $1,270. By 2024, the price rose to $5,570 per acre, “a fivefold increase,” according to Reed.

“Those questions need answers down the road,” Reed said.