HARTFORD TOWNSHIP, Ohio — The well sits at the edge of the woods, between the trees and Dave McCallion’s hay field. You can see the brine and oil tanks and the separator, painted bright blue, from Five Points Hartford Road, but the well blends in with its surroundings.

The metal is rusty. Blue paint is flaking off of the fittings. Cloudy green water bubbles up around the casing.

McCallion used to run his cattle in this field to graze after he’d taken off a second cutting of hay. He hasn’t let his cow-calf herd in there for several years now since the well started leaking. He’s worried a calf could get stuck in the water-filled trench around the well head. Or what if one of his cows takes a drink from that brackish water?

“Every time I cut hay, I go by that well,” he said. “I can smell the natural gas. I can see the stuff bubbling up through the water. It’s been going like this for years.”

McCallion said he’s tried for nearly six years to get something done about the leaking oil and gas well. He’s called the Ohio Department of Natural Resources, the agency that regulates the state’s oil and gas industry, repeatedly.

He gave up after a while, figuring it was just part of life living in eastern Ohio, where there are thousands of conventional wells like the one on his Trumbull County property, drilled into the Clinton sandstone. If the regulatory body tasked with enforcing the state’s rules on oil and gas couldn’t help him, or wouldn’t help him, who could? He couldn’t afford to hire a lawyer to do battle with the well owner or the state to compel either of them to do the right thing.

Then, in June 2022, Shawn Kacerski came to the Hartford Township zoning board meeting, where McCallion is a board member. During public comment, she stood up to speak and mentioned that a well was leaking on a property she and her husband recently bought.

“She wanted to know if it was zoning or the trustees (she should) talk to about gas wells leaking,” he recalled. “I told her she was barking up the wrong tree.” But he wanted to know if he could help her, anyway.

GRAY AREA

Kacerski’s story reignited McCallion’s drive to finally get something done about his well and now Kacerski’s. Between the two of them, they’ve reached out to the Ohio Attorney General’s office, the ODNR, the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency, the Sierra Club, local lawmakers and attorneys.

They hit wall after wall. Their wells, they found out, exist in a regulatory gray area.

The wells are leaking, but apparently not enough to present an urgent health, safety or environmental hazard. If that was the case, according to ODNR’s own policies, the department could have fixed the wells by now.

The wells haven’t produced any oil or gas for several years but aren’t listed as inactive by the state, which, by law, would require them to be plugged.

They’re somewhere in the middle, neither dangerous enough nor productive enough to do anything about.

The wells have an owner who is responsible for maintenance and repairs. If the wells were orphaned, meaning there is no responsible owner, the state could plug them or the landowners would be allowed to arrange for plugging.

Big Sky Energy, the company that owns the wells, has a history of non-compliance with state regulations. ODNR cited the company numerous times over the years for violations with its wells and infrastructure. The state agency used all of its available enforcement power against the company, and still, these problematic wells remain.

This is not a unique situation. There are wells like this all over the state, left over from decades of oil and gas exploration, much of which was unregulated or barely regulated. There are other operators like Big Sky Energy that break the law without facing real repercussions.

It’s the legacy of the land in Ohio, as much as farming is. Left in the lurch are landowners like McCallion and Kacerski.

“I’m not asking for thousands of dollars,” McCallion said. “I just want my (mineral) rights back and the well plugged. And the only reason I want my rights back is so they can’t drill any more wells.”

‘NOTHING WE CAN DO’

When Shawn Kacerski went to the Hartford Township zoning board meeting, she hadn’t planned to talk about the leaking oil and gas well on her property.

She had a burgeoning interest in her community since settling here in her husband’s hometown several years ago. She grew up in New Jersey. She met her husband, Steve, while living and working in Maryland. They moved back to Trumbull County in 2011, so Steve Kacerski could focus on crop farming with his family.

The Kacerskis bought a 90-acre property in Hartford Township, in December 2021, between Five Points Hartford Road and State Route 305. Steve Kacerski planted wheat the fall before and planned to tile it after the wheat came off in the summer.

On the property was a well called Woofter No. 1, as well as other oil and gas infrastructure. Pipelines, storage tanks, a pump jack.

By the time Shawn Kacerski was at the zoning board meeting in June, she’d called 911 about the well and infrastructure on that property twice.

In December 2021, shortly after they bought the property, a pipeline running through the land from another nearby well began leaking. She called 911. Someone from the company that owns the line came out to fix it, but they left the line above ground after it had been patched.

In April 2022, one of the neighbors and his children had been in the woods nearby and noticed the Woofter well head was leaking. Shawn Kacerski was alarmed and called 911 again, but getting first responders to the well was difficult.

“They had a hard time finding me,” she said. “Then, they couldn’t get back there. They had to borrow a side-by-side from the neighbor. Once they got back there, they said, ‘There’s nothing we could do.’”

Shawn Kacerski remembers being confused by the reaction. Isn’t it a big deal when a well head is hissing and blowing gas out of the ground? she thought.

“Here we are, thinking someone will fix this problem,” she said.

The ODNR sent the county inspector out to inspect the well. A report found “there was a casing clamp at the base of the tubing and it was leaking gas.” A notice of violation was issued April 26, 2022, because the well was “insufficiently equipped to prevent escape of oil and gas” and a fix was required within five days.

A follow-up inspection, on April 29, 2022, resulted in another violation notice, this time for “defective casing.”

As the couple bought and leased more land to farm, Shawn Kacerski wanted to become more involved in her new community. She joined the Hartford Optimists, a volunteer community service organization. She joined the Burghill Vernon Volunteer Fire Department. She also wanted to know how things worked. Where were her tax dollars going? Who was in charge?

So, as she stood there during public comment in front of the zoning board, in June 2022, she couldn’t help but ask about the well. Maybe these people knew how to help her, since dealing with ODNR was slow going.

“It’s like everybody knows about these, but that’s just how it is to live in the country,” Kacerski said. “I was told there are wells much worse than yours.”

THE CLINTON

Clinton wells are Ohio’s bread and butter when it comes to oil and gas production. More than 270,000 oil and gas wells have been drilled in Ohio since 1860, when the first commercial oil well was drilled, in Washington County. Of those, more than 80,000 are drilled into the Clinton sandstone. About half of those wells are still considered to be active today.

The first Clinton well was drilled in 1887, in Lancaster, Fairfield County. It was initially known as an excellent formation for gas production.

Clinton fields were developed around central Ohio, where the formation was closer to the surface. The subsurface rock formations underneath Ohio tilt slightly, getting deeper the further east you travel. That was what they could access with the technology of the day, a cable rig, or “spudder,” which cut into the ground using percussion.

The Clinton sandstone is known as a “tight formation,” meaning the rock is not permeable. It doesn’t allow the oil and gas to flow freely to the surface. These early wells were often “shot” with nitroglycerin as a way to increase production. It was dangerous but effective.

The first Clinton boom played itself out before the middle of the 20th century, but a second, much bigger boom was on its way, thanks to some advances in technology.

The rotary drill came along and allowed operators to drill deeper and access more of the Clinton formation across eastern Ohio. Hydraulic fracturing, developed in the 1940s, began to be used “with great success” in the Clinton in the 1950s to boost production, according to the ODNR’s Division of Geological Survey.

Then, during the energy crisis of the 1970s, the federal Natural Gas Policy Act offered tax credits for “high cost natural gas” production from tight sandstones like the Clinton. In the decade after the policy change, interest in the Clinton peaked. More than 4,300 wells were drilled into the Clinton in 1981. That was the most wells drilled in one year in the state’s history.

The well on Dave McCallion’s farm was drilled in 1982. His parents, Dave and Phyllis, signed a lease with Titan Energy Corp., of Cambridge, Ohio. The well was drilled at the edge of a field off of Five Points Hartford Road using an air rotary drill to a depth of 4,922 feet, according to ODNR records. It produced 10,895 Mcf of gas and 127 barrels of oil in 1984, the first year for which production records were reported with the state.

The Woofter well, about 2 miles away, was drilled in 1984, at a depth of 5,036 feet. It was named after the property owners at the time, Robert and Florence Woofter. The Woofters too signed a lease with Titan Energy Corp. The Woofter well was never particularly productive. Some years it didn’t produce anything.

Exploration in the Clinton slowed in the mid-’80s. The tax credit expired. Oil prices collapsed and natural gas prices stagnated. There was consolidation within the industry. It was part of the boom and bust cycle that’s played out innumerable times since people began extracting the earth’s bountiful natural resources from the ground.

The McCallion and Woofter wells changed hands, eventually being sold to Big Sky Energy, along with Titan Energy’s other wells in Trumbull County. Big Sky Energy owns more than 200 wells in seven counties.

Production of gas at the McCallion well remained steady over the years until 2016. The well produced 539 Mcf of gas and no oil that year. There has been no annual production reported to the state since 2016. That was the last year Big Sky Energy was permitted to produce oil and gas in Ohio.

‘FAILURE TO COMPLY’

Big Sky Energy is run by Robert Barr Sr. The company was started in 1997, according to state business records, and is based in New Concord, Ohio.

Farm and Dairy reached out to Barr via phone numbers listed for the business, but the lines did not work. Farm and Dairy also reached out to Barr through his attorney, Gino Pulito, but he did not respond to a request for an interview.

Most of what we know about Big Sky Energy and Barr come from public records and media reports, of which there are many. In the last decade, the company has made the top 10 list four times for operators with the most violations against them. It topped the list in 2016, with 131 violations. That was the year the company was ordered by a judge to cease operations, and the company’s infrastructure was scrutinized more closely.

One ODNR order from 2012 notes that “Big Sky Energy has numerous violations for failure to comply with R.C. Chapter 1509 and Ohio Adm. Code 1501:9,” the laws and administrative rules that empower the department to regulate the oil and gas industry.

Big Sky Energy has been involved in many lawsuits and conflicts with landowners and residents who live near its oil and gas infrastructure. In March 2007, the company was accused of letting sediment runoff from a drilling site leak into lakes at a housing development, in Plymouth Township. An EPA investigator said the muddy runoff killed fish in the lakes.

Barr told the Ashtabula Star Beacon at the time the “EPA guy is a liar and full of B.S. The fish suffocated because the lake froze over and there’s not enough water in the pond for all those fish.”

In a follow-up story, Barr softened his response to the complaint but still denied any responsibility for the fish kill.

“If the (ODNR) samples show we killed some fish and they tell us we will have to replace the fish, then we’ll replace them,” he said. “But nobody has told us that.”

In July 2015, a Big Sky Energy oil tank near the Ohio-Pennsylvania border leaked hundreds of gallons of crude oil into a tributary of the Shenango River. The spill, from a tank on Orangeville Road, in Brookfield, Ohio, forced residents of three counties to conserve water after the nearby water treatment plant had to shut down.

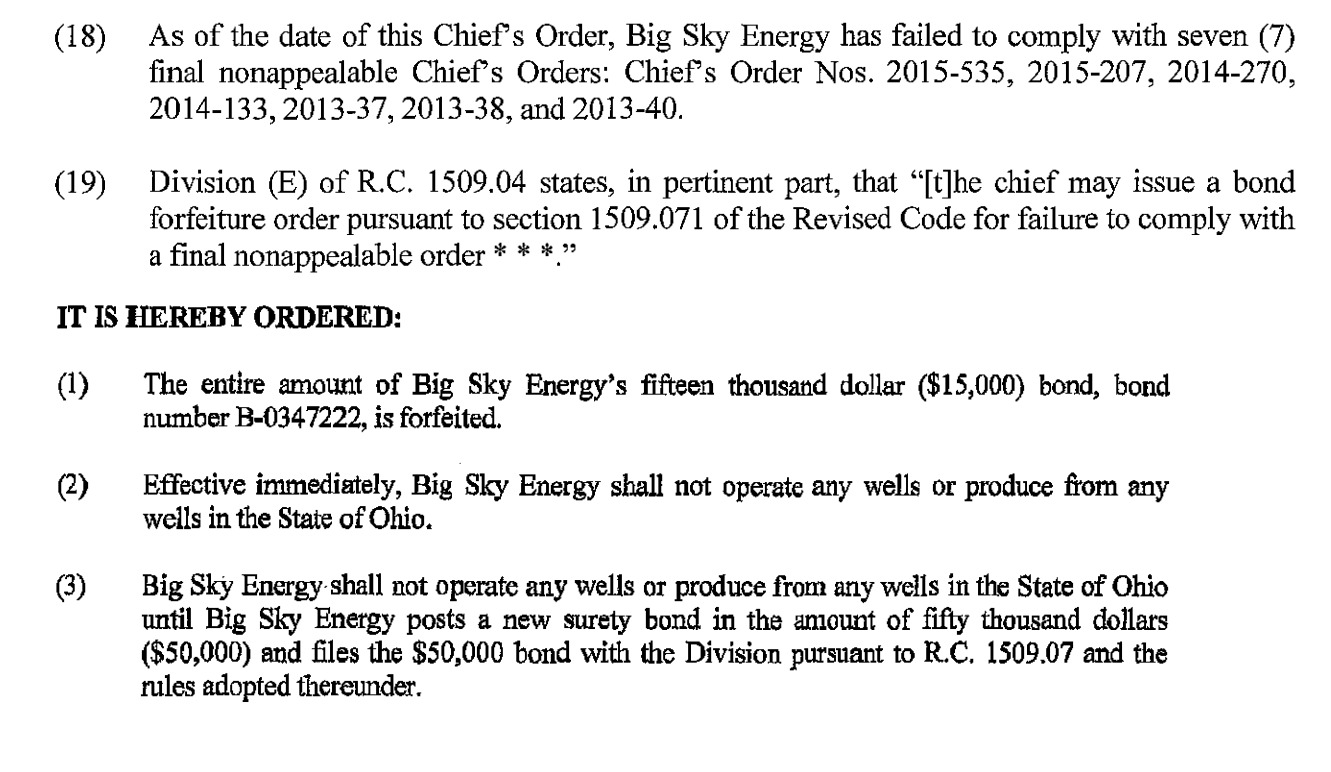

ODNR ordered the company to suspend operations in November 2015 after it failed to maintain liability insurance, as is required by the state of all oil and gas operators. The department revoked Big Sky’s bond in March 2016 and ordered it to cease operations after it failed to get insurance and comply with seven previous orders.

An ODNR Division of Oil and Gas Resources attorney confirmed to Farm and Dairy the company still does not have current liability insurance or a surety bond.

The Ohio Attorney General’s office has taken the company to court on at least three occasions on behalf of the ODNR. One of those court cases — filed in Trumbull County in 2016 — was the tipping point.

Then-Attorney General Mike DeWine filed for a temporary restraining order against Big Sky Energy after one of the company’s gathering lines leaked oil into a tributary of Yankee Run Creek, in Brookfield Township. A Trumbull County Court of Common Pleas Judge issued the temporary restraining order, in April 2016, requiring Big Sky Energy to suspend all oil and gas operations within the state until it obtained state-required liability insurance.

The company tried but failed to get insurance. Barr said during a hearing in September 2016 that they didn’t have money to properly remediate the site of the spill because of a downturn in the industry.

The judge ruled in favor of the state in October 2017 and hit the company in December 2017 with a civil penalty of $141,700, or 1% of the statutory maximum of $14.2 million. The same day the fine hit, Barr filed for personal bankruptcy. The case was stayed due to the bankruptcy, but a judge later ruled Big Sky Energy and Barr were still liable.

FAILURE BY DESIGN

Big Sky Energy and its pattern of non-compliance are not unique in Ohio, according to various sources in and around the oil and gas industry that Farm and Dairy spoke to about the situation.

This sort of blatant disregard for the rules was found to be common among conventional oil and gas well operators in neighboring Pennsylvania as well. The Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection released a report earlier this year that found more than half of conventional well operators in the state failed to report annual production data and mechanical integrity inspections for wells. Another common violation issued was “failure to plug a well upon abandoning it.”

The DEP report said a “significant change in the culture of non-compliance as an acceptable norm in the conventional oil and gas industry will need to occur before meaningful improvement can happen.”

Some of this culture is due to neglect, regulatory agencies spread too thin, and some of it is by design, according to Ted Boettner, a senior researcher with the Ohio River Valley Institute. Boettner has authored reports on the impacts of orphan wells and abandoned mine lands in Appalachia.

Conventional wells don’t get enough attention from regulators, Boettner said. For example, the ODNR is overburdened and understaffed, like most public agencies, he said. With their finite time and resources, they focus their efforts on wells that are being drilled, particularly high-volume deep unconventional wells like those going into shale formations.

“They’re following those rigs around,” he said.

To make sure oil and gas companies are financially responsible for plugging wells, they’re required to submit a bond with the state, according to the ODNR. The bonding requirement is $5,000 for one well or a $15,000 blanket bond for two or more wells.

The average cost to plug a well in Ohio ranges widely. Some estimate it to be around $20,000 per well, while others put it closer to $100,000.

With such a disparity between regulation and reality, it would seem as if there was never the intention for all wells drilled to be plugged. Boettner said it’s part of the business model of the industry. There are few conventional oil and gas operators out there that could afford to plug all of their wells, he said.

“They know they’re not going to be held accountable for the wells that are unplugged,” he said. “If they did, they’d all go out of business, and the state doesn’t want that.”

Plugging and abandoning oil and gas wells has “historically been conducted as an afterthought,” according to a 2011 document put out by a National Petroleum Council working group. The council is an industry advisory committee to the U.S. Secretary of Energy.

“The traditional view of [plugging and abandonment] is that it is a necessary evil and should be done as cheaply as possible,” according to the paper, whose authors included representatives from Chesapeake, ConocoPhillips, Chevron, Halliburton and the U.S. Department of Energy.

The document points out that regulation in the industry began as a way to protect future resource development, but more recently, realizes the environmental benefits of plugging.

For its part, the Ohio oil and gas industry maintains that most operators follow the rules not only because it’s their obligation but it’s how they keep a productive business environment. The Ohio Oil and Gas Association, the state’s oil and gas trade association, told Farm and Dairy being a good partner with landowners and the community is an “absolute must” and essential for a healthy oil and gas industry. Big Sky Energy is not a member of the Ohio Oil and Gas Association.

STILL LEAKING

McCallion had a few issues with the well over the years. One of the pipelines leaked in 2006. It was fixed after a few days. McCallion called about a brine leak at the production tank, in November 2013. The leak was repaired several days after it was reported.

A county inspector visited the well in April 2016, after the Trumbull County restraining order was issued. The well was operational, but needed a few things to be fixed. The hammer unions on the casing and tubing flow lines had oil staining, indicating they needed to be tightened. The production chart needed to be changed. It was overprinting previous production data. A follow-up inspection, in September 2016, found the well not in production.

McCallion reported a leak at the gas well on his property in May 2017. He noticed it when he was preparing to take the first cutting of hay off that field.

According to the official ODNR complaint, McCallion said “he noticed gas leaking around the surface casing at the well located at this property.”

McCallion was advised that the issue would be referred to the county inspector for follow-up. When a county inspector visited the well, on May 22, 2017, he found it in much the same condition it’s in today.

“I found a hole dug around the well filled with water. The water was bubbling from gas leaking from the well,” the inspector wrote in his report.

Big Sky Energy is listed as the well owner, but the inspector said in the report that an identification sign posted at the well listed Vortex Energy LLC as the owner. The inspector spoke to a well tender, who said he knew about the leak and would move a rig there to fix it as soon as he was done working on another well.

The inspector issued a violation notice that Big Sky Energy needed to repair the leak by June 2, 2017. The inspector visited the well again two days later after the first compliance notice was issued to find nothing changed. It would remain more or less the same for the next five years.

The ODNR would not comment about anything specific regarding Big Sky Energy for this story, citing open litigation, but the course of action it took for McCallion’s well is laid out in the inspection reports and complaint log, which Farm and Dairy acquired through a public records request.

Inspectors continued to check the well and report on its status, and it continued to leak. The well tender, when he could be reached, told ODNR repeatedly he would get a rig to the site as soon as he could to fix it. There were various delays, he said.

An inspection report, from March 20, 2018: “The hole is full of water and is bubbling from the gas leak.”

A report, on Aug. 31, 2020: “The well was still leaking. Bubbling in the standing water around the well’s 4 1/2 inch casing was observed.”

A report, on Feb. 9, 2021, notes that “previous messages left with Big Sky Energy, Inc., have yielded no changes to the well site.”

An inspection, on Oct. 11, 2022, found that in addition to the leak at the wellhead, the brine tank had overtopped and leaked onto the ground. New violations were issued, this time for failure to keep the dike around the storage tanks free of water or oil and for having a defective casing and leaking well.

A visit to the well on March 15 by Farm and Dairy found it still leaking. The water around the casing was partially frozen, but it was still bubbling.

EXHAUSTED

In a perfect world, here’s what should have happened with the McCallion well, according to various industry experts Farm and Dairy talked to about the circumstances: Big Sky Energy should have fixed the leak.

If the company decided it was too much trouble to fix the leak, it should have plugged and abandoned the well. If Big Sky did not comply with the order to fix the leak, the ODNR could have, and probably should have, done more to fix the problem.

According to ODNR, if a violation isn’t addressed, its division of oil and gas can escalate enforcement. A chief’s order may be issued. The operator may be fined or possibly even face jail time, depending on the violation. The division may negotiate a compliance agreement with the operator. The division can also refer violations to the Ohio Attorney General’s office.

How quickly any of this happens is up to the oil and gas division. Things that factor in are the type and severity of the violation, frequency of the violation and the operator’s willingness to comply, ODNR said.

Wells could be plugged if there is an “imminent health and safety risk” at a well site or if the owner does not initiate a corrective action within a “reasonable period of time,” ODNR said. These things are determined on a case-by-case basis by the division’s field enforcement team.

The division has gone through these steps with Big Sky Energy before, with varying levels of success.

If a landowner has exhausted all options through the state but wants to continue pursuing the issue, they can choose to hire an attorney to take legal action of their own, said Dale Arnold, Ohio Farm Bureau’s director of energy, utility and local government policy.

He said he deals with oil and gas issues just about every day in his work, explaining the nuts and bolts in plain language to members and referring them to other resources, like the farm bureau’s attorney referral network.

Hiring an attorney may be the answer to the problem of “what should a landowner do when the system fails them,” but it’s not an option that is affordable or accessible for everyone. Nor should it be the best answer for landowners dealing with contracts signed and wells drilled decades ago by other people.

No one seems to have a good explanation as to why the McCallion well hasn’t been fixed, other than it’s just not an important enough issue to anyone, other than Dave McCallion.

Arnold said he often speaks with landowners who are in situations similar to the one McCallion is experiencing. From what he’s seen, when there is a real emergency with a well, things get done “very, very quickly.” Otherwise, ODNR has to triage its issues, he said. Wells that are leaking but stable are on the list, but it’s a long list.

In addition to non-compliant operators, ODNR is dealing with a massive number of orphan wells, or abandoned wells without a legal owner. There are an estimated 36,000 to 66,000 orphan wells in Ohio. The department beefed up its orphan well program in the last couple of years, but in large part by contracting out much of the work that used to be done in-house, Boettner said.

“The people that work at these agencies do the best job with what they have,” he said.

Arnold said the non-compliance issue may be an indication that the ODNR needs more, or sharper, enforcement teeth. That would have to come through legislative change.

Boettner argues many of these problems could be fixed with money. Boettner authored a report called “Stayin’ Alive: The Last Days of Stripper Wells in the Ohio River Valley,” in which he explored the coming environmental and economic catastrophe from marginal, or stripper, wells that are producing little oil and gas, and will soon need to be plugged. Ohio has 35,377 such gas wells.

In the report, Boettner suggested that a small fee on production — between 3 and 7 cents per Mcf of gas produced — deposited into an escrow account could go a long way toward paying to plug wells if operators walk away from them. States could also require bonding amounts that reflect the true cost to plug wells, Boettner told Farm and Dairy.

“This didn’t have to happen,” he said. “We have to stop coddling these companies. They have to take responsibility for their own actions. They are passing the cost onto all of us.”

CURSED

The Woofter well on the Kacerskis’ property was eventually patched, five months after the leak was reported to the ODNR, but not before it killed a deal for the couple to lease that ground for a solar farm.

Last spring, a solar development company approached the Kacerskis about leasing some of their land. Steve Kacerski suggested the land they’d just bought, the 90 acres on Hartford Five Points Road. It was flat, clear and an electrical substation sits across the road. It’s exactly the kind of property ideal for solar farm development.

Steve Kacerski disclosed the old oil and gas infrastructure there. The developer seemed to think they could work around it. The developer made it out to the property, in May 2022, to get a lay of the land, something they typically do before finalizing lease paperwork. A few weeks later, the deal was dead.

“We believe it is going to be an environmental nightmare trying to get this built with the leaking well,” the developer said, in an email to Steve Kacerski, dated June 2. “The risks are too high, and therefore we will need to pass on developing this site.”

An ODNR inspection report, from Sept. 23, 2022, found the well was no longer leaking: “No audible gas leak was observed.” The well was not leaking at a Nov. 2 follow-up inspection.

Shawn Kacerski checked the well in November while she was at the property and found an empty can of J-B Weld epoxy discarded on the ground near the casing. The litter was a reminder that one problem is fixed, but it was done so in a careless way. Still other problems remain.

“This property is cursed,” she said.

She used to think there was a system in place that would hold people and companies to account. She’s more cynical now, having seen the system in action.

“This isn’t a Kacerski Farms problem. It’s not a Bob Barr problem. It’s an Ohio problem,” she said.

(Reporter Rachel Wagoner can be reached at rachel@farmanddairy.com or 724-201-1544.)

ODNR did a great job plugging my orphan well last year. Your article was very important for all to understand. Thank you.