Living in roughly the same era as European and American contemporaries such as Vincent van Gogh and Winslow Homer, Swiss-born scenic artist Ferdinand Brader captured rural life in Ohio and Pennsylvania in a uniquely detailed way.

The largest exhibit of more than 60 of the 980 Brader drawings known to have been made will be held Dec. 4 through March 15 at the Canton Museum of Art, the William McKinley Presidential Library and Museum, and the Little Art Gallery at the North Canton Library. The exhibits, assembled from drawings discovered by local Brader expert Kathleen Wieschaus-Voss, will examine both Brader’s artistic and historical importance.

Related story: Finding Ferdinand Brader

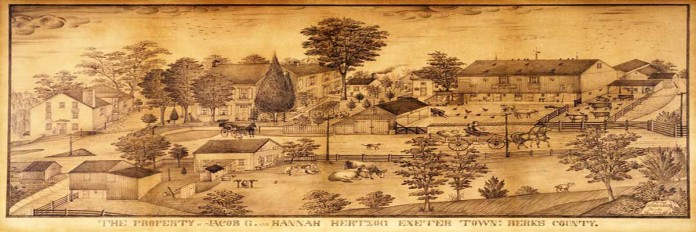

Made with pencil on inexpensive cartridge paper, Brader’s works are as mysterious as they are ubiquitous. Each one included the owner and location of the farm, as well as its numerical order in relation to previous drawings — number 980, drawn in 1895, being the last known work — creating an almost literal map of his travels across Pennsylvania and Ohio.

Fortunate find

The 1886 Brader owned by Russell Newburn, of Alliance, is of the Moulin Avenue farm of his great-great-uncle and aunt, John and Katharina Bichsel.

The drawing is perhaps the most intricately detailed views of a late 19th century cheese-making operation known to exist. Newburn said it hung in his grandmother’s farmhouse for years, until the family decided to “modernize” in the 1940s.

As a boy, Newburn found the drawing in his grandmother’s attic, wrapped in leftover wallpaper. After doing some summer work on the farm for his grandfather, Newburn negotiated taking the drawing in lieu of payment. “I always had an interest in old things,” Newburn said, “and what is unique to Brader is the detail and his perspective.”

Stunning detail

Others in the area have had similar stories. After owning it for years, Phil Harlan began researching his 1885 Brader, of his great-great-grandparents’ Beutler farm on Bandy Road in Alliance, after reading about Wieschaus-Voss’s search for lost Braders.

“I called Kathleen and told her, ‘well, I’m standing here looking at number 466’,” Harlan said. The Brader had been a family treasure for some time, Harlan said, though no one realized its true artistic and historical importance.

“My mom remembers her mom flattening it out on the (dining room) table and taking it to be framed,” he said. “But we didn’t even talk about who drew it.”

When he began researching other family photos of the Beutler farm, some taken only seven years after the Brader drawing had been made, the detail of the drawing was revealed. Despite its somewhat primitive, folk art style, the massive, birds-eye view of the farm includes accurate depictions of both farm equipment and buildings and Harlan’s relatives.

Harlan has, in fact, counted the number of chimney bricks on both the 1892 photograph and the Brader drawing of the Beutler farm house seven years earlier. They match. Based upon the numerical order of drawings immediately before and after, Harlan surmises that Brader may have spent the winter of 1895 with his family, and that his Brader may be the last one the artist drew that year.

Delicate treasures

To date, Bob Lodge, president of McKay Lodge Conservation Laboratory in Oberlin, Ohio, has worked to preserve more than five Brader drawings. While Brader drawings have fetched up to $30,000 at auction, most are extremely fragile, due in large part to the type of cartridge paper used by the artist.

Lodge explained that the combination of acidic compounds in the paper, the wood backing of the frames, and the fact that Brader finished his drawings by applying buttermilk as a fixative, has resulted in both a darkening of the more than 100-year-old drawings and extreme fragility.

“When exposed to light, these things can just turn to dust,” Lodge said. “And most that we see are in really bad shape.” The process of removing accumulated acids by “washing” a drawing, Lodge said, can take up to five days and cost $5,000. Owners who cannot afford such an investment should keep the drawing out of light, in low humidity, and off the floor, he said.

While Lodge described Brader’s work as “primitive,” he said it is among the best examples of that style. Lodge added that it is also apparent that the artist truly enjoyed his work. “One thing that is unique is the size of his paper, the remarkable scale and his ability to get a birds-eye view — he wasn’t in a hot air balloon,” Lodge said.

“And (Brader drawings) provide very interesting information about farmland in Ohio and Pennsylvania such as the laying out of buildings in relation to crops. I think the exhibit will be interesting to farmers and other property owners who wonder what a building on their property was used for.”

Historical importance

Max Barton, marketing director at the Canton Museum of Art, said that while Brader also drew other scenes of factories, train depots, churches and homes, his farm drawings are a treasure trove of information about the development of farm machinery and tools, types of crops, and the use of outbuildings on farms near or at the turn of the 20th century.

“I would not be so bold as to say he was the only one,” Barton said of Brader’s style, comparing it in general to more widely known work such Homer’s American Civil War battlefield sketches. “But his work was unique in giving a view of life in a certain area.

“A piece of art, to the artist, is a snapshot in time. A Brader is a view of American family life and the landscape of Ohio and Pennsylvania at that time.” Kimberly Kenney, curator at the McKinley Presidential Library and Museum, said that from an historical perspective, the drawings represent a singular preservation of local heritage.

“They look similar, but there are a number of different things in each — one even has a beehive,” Kenney said of the detail in Brader’s work.

“We hope (visitors to the exhibit) look very closely.” Elizabeth Blakemore, curator at the North Canton Public Library’s Little Art Gallery, agreed. “A Brader is not something you normally see, and it reflects how he survived,” she said of the exhibit.

“I think it’s important to make the community aware of his legacy and preserve what he did.” As a Brader owner, Newburn said that he too feels the importance of Brader’s work far outweighs the motivation behind it.

“I don’t know what his goal was, but what impresses me is that he has preserved American life in this part of the country,” Newburn said. “In modern-day language, he was an ethnographer — he documented people.”

Related story: Finding Ferdinand Brader