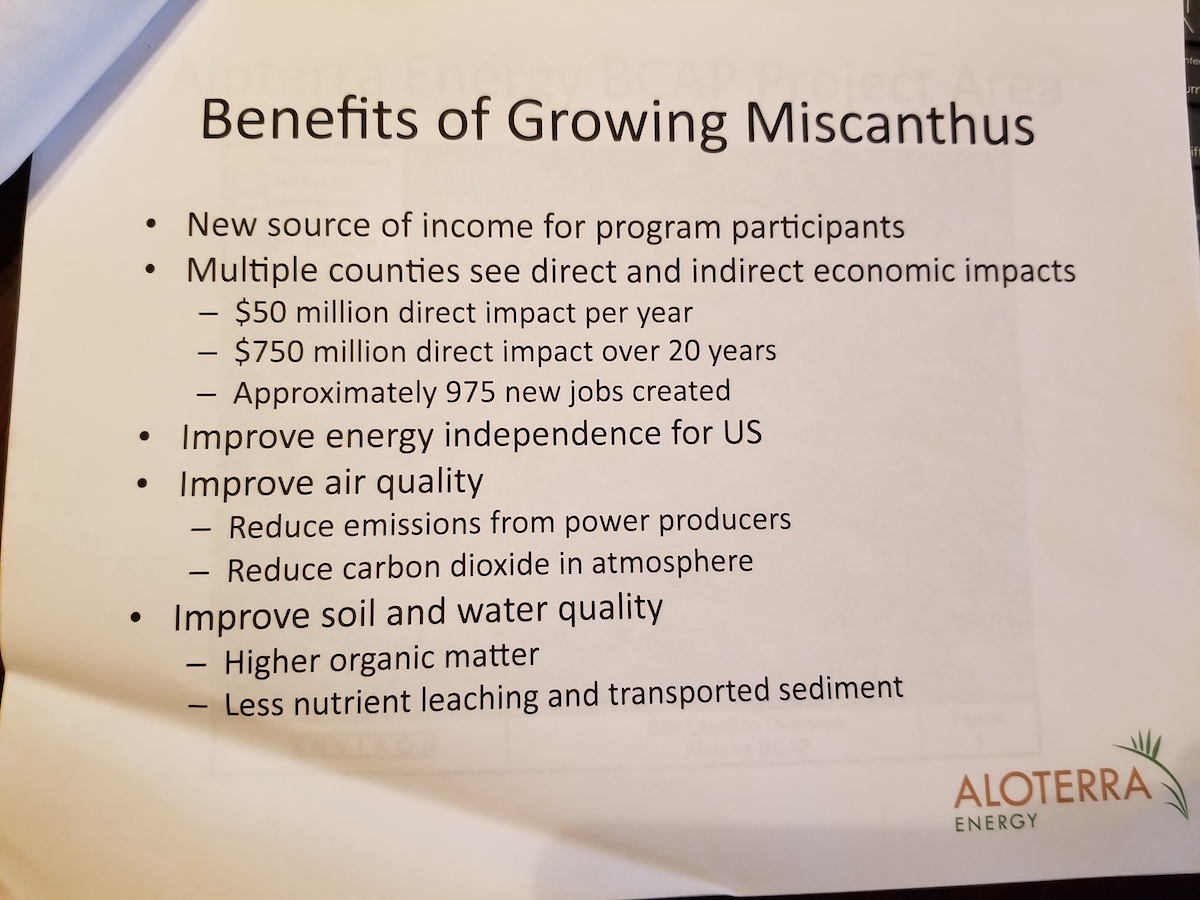

ALBION, Pa. — Miscanthus was pitched a decade ago as a wonder crop. Growing the woody, perennial grass could bring farmers and landowners a new source of income, improve air quality, improve soil and water quality, create jobs and maybe even help the U.S. move closer to energy independence.

That was the proposal laid out by Aloterra, a company that received millions from the U.S. Department of Agriculture to establish giant miscanthus in the region. Dozens of landowners in northeast Ohio and northwestern Pennsylvania signed on with Aloterra to grow this up-and-coming crop.

“We went into this, we thought it was a really good idea,” said Deb Parknow, a miscanthus grower, in Albion, Pennsylvania. “I was proud to be a part of this when it first started.”

The venture was off to a promising start, but the company struggled to recover from early setbacks. The intended market for the crop — cellulosic ethanol — didn’t develop. Aloterra tried other things, but the money ran out, and it didn’t pay its farmers.

Now, some frustrated farmers have gone through great lengths to remove the hardy plant from their fields. For those left, the people behind Aloterra want to develop the crop in this area. They have a new company, Warrior Marketing LLC, and a new idea for how to make miscanthus profitable.

“We’re going to take care of everyone that’s been with us in the past,” said Jon Griswold, former chief executive officer of Aloterra. “If I get the opportunity to get back what I believe these farmers deserve, I’m going to get it back to them. I’m not walking away from anything I owe people.”

A new opportunity

To the Parknows, growing miscanthus seemed like a good way to make a little more income from their farmland.

Deb and Don Parknow live in Erie County, on a small farm they inherited from Don’s family. They used to raise cattle, but Don gave it up as he got older. They’d just been making and selling hay.

The couple went to a presentation that laid out the entire program. Aloterra was selected to administer the USDA Biomass Crop Assistance Program, or BCAP, in the region that included Ashtabula, Geauga, Lake and Trumbull counties, in northeast Ohio, and Crawford, Erie and Mercer counties, in northwest Pennsylvania.

The company received $5.7 million from the USDA in 2011 to establish miscanthus in that area. The goal was to get about 5,300 acres planted.

BCAP was created by the 2008 Farm Bill, as a way to encourage biomass production to be used for bioenergy and other bioproducts. The thought was that if the USDA could get people to grow the crops needed to create cellulosic biofuels, it would give the industry the jump start it needed. The program paid up to 75% of the cost to get stands of miscanthus established, $45 per dry ton harvested for two years and $40-$100 in annual rent payments, with reductions based on how the crop was used.

By Deb Parknow’s estimations, they could make nearly $10,000 a year from the program.

“We thought it’d be a good way to pay taxes and insurance [on the farm],” Deb Parknow said. “We signed a five-year contract with them initially.”

The Parknows enrolled 22 acres in the program. Aloterra planted, harvested, processed and marketed the crop. It required special equipment to plant and harvest the Parknows didn’t have.

Aloterra paid growers by the tonnage that was harvested from their fields. Once the plant was mature, they expected to harvest about 10-12 tons per acre. The company deducted costs from the Parknows’ payment.

The first few years they wouldn’t make as much. By year five, they could expect an average income of about $404 per acre, according to an informational packet the Parknows got from the initial meeting with Aloterra.

All the Parknows had to do was prepare the land for planting and monitor and maintain the fields. The first rhizomes went in fall 2012.

“I think they cut it twice, and we got paid very little for it because there wasn’t a lot of tonnage to it,” Deb Parknow said. “It was nowhere near what they said it would be. Then, I couldn’t get a hold of them. This whole time we’ve been under contract with them, they’ve been hard to deal with.”

Big ideas

Aloterra was founded in 2010 with some lofty goals. The self-proclaimed “next generation agribusiness” aimed to develop miscanthus as a new source for cellulosic ethanol.

Giant miscanthus is a sterile hybrid, warm season grass native to Asia. The fast-growing reed-like plant can reach 10 to 12 feet in height in one growing season. Stands of miscanthus can last up to 20 years. Part of its appeal was that it could be grown on marginal land, said Andrew Holden, Ashtabula County extension educator with Ohio State University. The crop is harvested in the winter during its dormant period.

The company worked with about 90 landowners and planted about 4,600 acres.

But the cellulosic biofuels refineries never appeared, even after the biomass to supply them did. As BCAP got started, so too did the shale gas boom in eastern Ohio and western Pennsylvania. Suddenly, cultivating better sources of renewable energy wasn’t as dire, with a glut of local natural gas on the market.

“The processes that we thought were available to convert this to ethanol really weren’t there,” Griswold said. “There had been some miscalculations by the people touting the process.”

Aloterra found other uses for the miscanthus. It opened a facility in Andover to produce an absorbent product that was sold to the oil and gas industry to soak up waste water and other drilling fluids. A facility opened in Ashtabula to produce biodegradable clamshell takeout containers using the plant’s fiber.

“The biggest issue was the market was way slower to develop than we anticipated,” Griswold said. “We tried to go in several different directions to get one of them to start working well. And it’s like many startups, you end up short of funds.”

Undercapitalized

The Parknows’ first contract with Aloterra expired in 2017. They were given the opportunity to stay on as growers or to lease their land to the company.

They chose to lease the land for about $90 an acre for five years. That would bring in about $1,900 a year.

Deb Parknow said they were paid twice and only got $3,000 total. She called Aloterra, but heard back. They would occasionally get letters from the company.

One letter, dated Oct. 21, 2019, opens with the sentence, “We are making every effort to catch up on all unpaid land leases and producer material.”

It cites the difficulties the Aloterra was having with the downturn in the oil and gas industry and issues with its Ashtabula production facility.

Griswold admits they didn’t pay people the last couple years. Aloterra didn’t have the money. Federal monies supporting the venture also dried up.

Aloterra went into court-appointed receivership, an alternative to bankruptcy, in early 2020, after it defaulted on a loan from Erie County Investment Co. Aloterra owed its creditor more than $9 million.

“With hindsight, they were undercapitalized to undertake such an innovative plan,” a court document states.

The company reorganized and is operating under the name Warrior Marketing LLC. It’s still trying to make a go of it with miscanthus.

Working with Argonne National Laboratory and the University of Chicago, Aloterra developed a process to get cellulose nanocrystals from miscanthus on a commercial scale. The nanocrystals have some promising uses to strengthen other materials while keeping it light, Griswold said. The project earned the groups a 2019 R&D 100 Award, an innovation award presented by R&D Magazine.

That’s the long term goal. The company needs funding to get a plant established in the region to capitalize on the nanocrystal processing. Right now, the company is selling miscanthus as an absorbent.

Starting over

Some farmers have already gotten rid of their fields of miscanthus. Holden said it’s not easy or cheap, but it can be done. The towering canes of miscanthus need to be mowed down, then allowed to grow back about 10-12 inches before applying glyphosate. Then, it can be tilled under.

The hard part for some landowners may be finding the equipment large enough to mow it.

“Some people have popped tractor tires trying to mow miscanthus,” Holden said.

Griswold said the company sent letters to all the landowners Aloterra worked with before, letting them know about efforts to develop a new market for miscanthus. Some people have already signed back up, he said. The company is harvesting miscanthus this winter, less than 1,000 tons on the first run, he estimated.

Working with Aloterra was frustrating and costly, as their once profitable hay fields are now choked with miscanthus, but the Parknows still believe in the crop. It’s a beautiful plant with many possibilities.

Deb Parknow said she would consider working with Warrior Marketing, as long as it would pay her what she is owed this time around. It feels like her only option.

“It’s sitting here doing nothing, and I can’t get rid of it,” she said. “I’m stuck. I’m completely stuck. If I could get rid of it easily, I would.”

(Reporter Rachel Wagoner can be contacted at 800-837-3419 or rachel@farmanddairy.com.)

I worked for Aloterra in Ashtabula for a few months. It was an absolutely HORRIBLE place to work. Nothing was ever fixed properly so the machines could run properly to produce product that wasn’t scrap. Quality details seemed to change daily if not hourly and by person to person on the quality team. Money was always missing from paychecks. Entire building constantly full of bugs. Also had main fire exits boarded up on the forming side… Should I also mention the letters I’ve received about the lawsuits they’re currently looped with… ~sips my tea and looks away~ they had the potential to be a really great company. Shame they cared about their own pockets instead of creating a good company.