A curious thing about those apple butter makin’ parties – unlike most frolics and bees that occurred across the Ohio Country in the 19th century, this party took place the night before the real work began and not during the labor-intensive activities which encompassed most of the following day to complete.

The primary purpose of the apple butter party was to prepare the huge number of apples that would be required the next day for the big cooking; therefore, the first step in the process was to sort through the many bushels of apples that had been brought from the family’s orchard – and probably those of participating neighbors as well — to the cooking site. The apples had to be given a good look-over to detect rotten spots or, even worse, worms. No one wanted worms cooked into their apple butter. Apples that were rejected were usually fed to the pigs or simply used by children for throwing contests or an apple fight. After being washed, the apples to be used had to be peeled and then cored.

Peeler technology

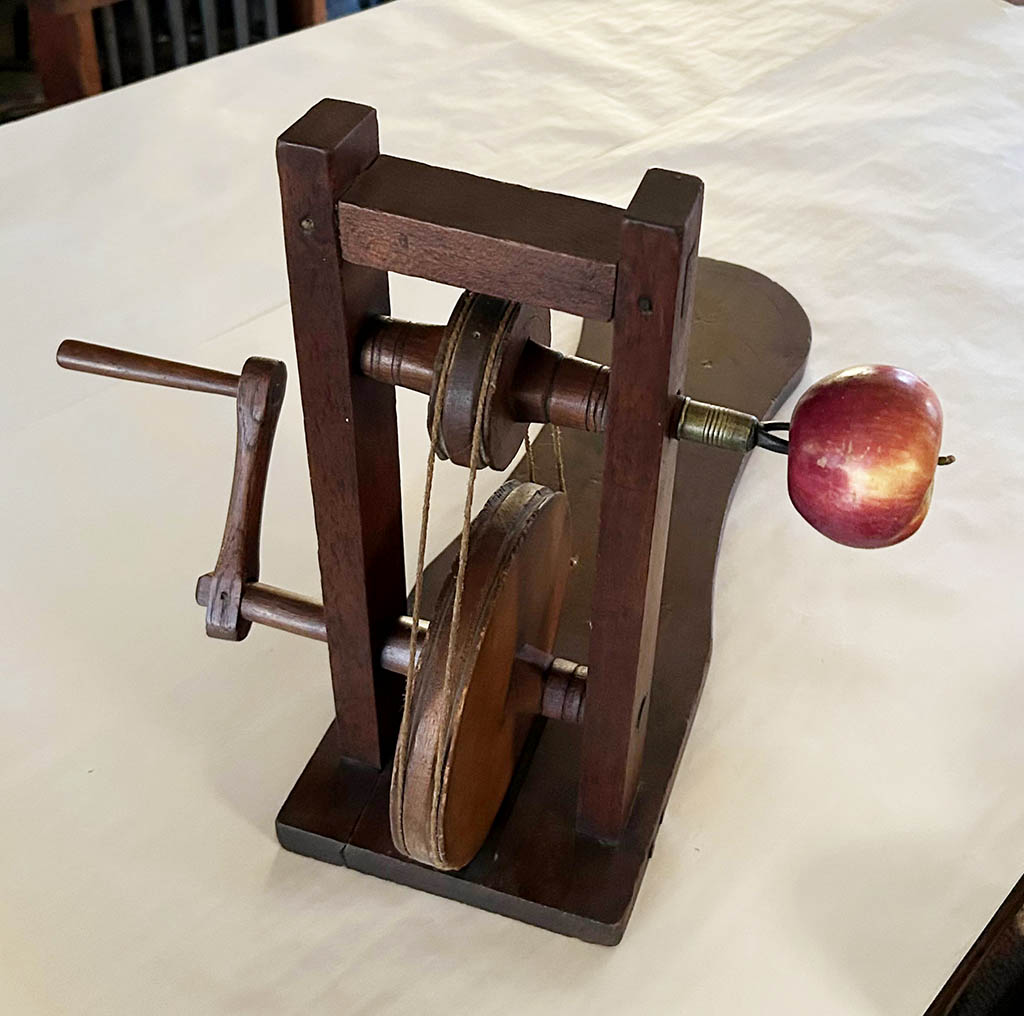

Entire books could be written about the vast numbers of ingenious mechanical wood and iron apple peelers that were invented across the length and breadth of the frontier. It seemed that every settler with a modicum of engineering, woodworking and blacksmithing skill wanted to invent what they perceived as being the most efficient (and oftentimes complex) device for doing the extremely simple job of peeling apples. A good display of these early apple peelers would tease the imagination of the most accomplished technical engineer for a protracted time since many of these primitive machines revealed the builder’s acumen for mathematics, geometry and physics.

In its simplest form, the apple peeler consisted of a large hand-cranked driving wheel which was connected by a cord or leather thong to an axle of small diameter, on the end of which was mounted a wrought iron fork which impaled the apple to be peeled. The drive wheel and axle were mounted on a board 2 feet or so in length. The operator sat on the far end of the board, away from the cranking mechanism. He then turned the crank of the drive wheel, making the apple spin on the axle. As it did so, he used a knife to continuously peel the skin off the fruit.

This simple design, however, seemed to allow much room for improvement in the eyes of many would-be inventors. Woodworkers who felt the drive wheel and cord method were too simplistic worked to come up with every imaginable type of drive assembly, ranging from direct drive wooden cogs and gears to screw-type contraptions that they felt more efficiently engaged the axle. And if all that wasn’t enough, some of them created peelers with integral automatic apple ejectors. After an apple was rotated a certain number of times during which it was peeled automatically, a spring-loaded arm struck the fruit, knocking it off the iron fork and into a waiting bucket.

Inventors

A settler in Wayne County, Ohio, who displayed a particularly outstanding sense of ingenuity in developing mechanical apple peelers was William Ewing of Congress Township. Ewing, who arrived from Stark County in 1812, opened the very first store in Wayne County. He apparently enjoyed toying with the design of mechanical apple peelers and at least a dozen of his primitive examples are known to have survived.

Another businessman who enjoyed building wooden apple peelers was David Mill Pease who had a wood turning business in Concord Township, Lake County, Ohio, in the mid-19th century. Pease, who expertly turned out a vast array of wooden containers of all descriptions (Peaseware) which are now widely collected, also crafted mechanical wooden apple peelers. These are readily identifiable by an urn-like finial on the peeler portion, which was the signature element of many of his pieces.

The rest of the work

So, with a number of mechanical apple peelers now present and whirring away, it was time to core the apples and cut them into sections for cooking the following day. And just like the mechanical apple peelers, a vast variety of inventive devices were created for apple coring and slicing. Many of these devices worked by lever action with plungers driving the peeled apple through circular iron cutters which separated it into six or eight sections before falling into a bucket below. Other types utilized cylindrical sheet iron tubes which levers drove vertically through the center of the apples to remove the cores.

Finally, a plentiful supply of cider, which the apples would cook in, was brought to the site. Like the apples themselves, the cider had to be pressed from a combination of sweet and tart apples for just the right flavor. Some settlers had smaller cider presses for their own use, while some groups of pioneers got together to construct larger presses which they could all use.

All of this sorting, peeling and coring was light work that allowed time for plenty of socializing as the news and gossip of the day in the evolving community was traded while the children played with their friends. The real work would begin bright and early the following morning.