Why were roofs put on bridges in the first place?

We still have a couple of covered bridges here in Columbiana County and surviving examples exist around the country. Recently, a few of us were discussing the reason for covering a bridge with a roof and sides. There were several different theories so I decided to investigate.

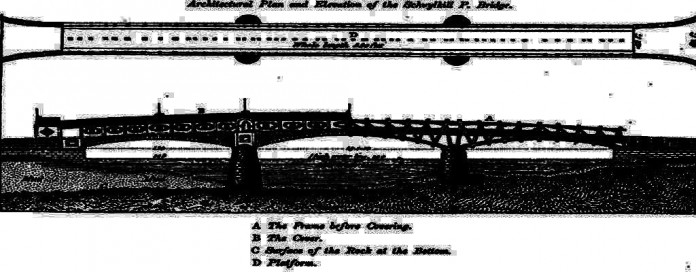

The first covered bridge in America is believed to have been the High Street (later, Market Street) Bridge across the Schuylkill River in Philadelphia.

Prior to 1776, a ferry provided the only way to cross the river at High Street, but the Continental Army, and then the British Army built pontoon bridges at the location.

After the war, there had been several floating bridges built of planks laid across floating logs anchored by cables to the banks, but these interfered with boats traveling on the river and were subject to being swept away by floods.

In 1798, an act was passed by the legislature that authorized the formation of a company to solicit subscriptions to build an ornate stone arch structure with two masonry piers in the river bottom.

Work on the piers began in 1801 and was completed in 1804 after much difficulty and great expense due to the depth of the water on the western side and mud and uneven rock on the river bottom.

Wood was cheaper

An Englishman named William Weston submitted a good plan for a stone bridge, but it was realized that stone would cost too much, so proposals for both metal and wood structures were sought. Weston then designed a likely looking iron structure, but it was still quite expensive and there were no available workmen familiar with iron work, so it was finally decided to use wood, which was plentiful and cheap, for the structure.

Timothy Palmer (1751-1821) was a Massachusetts man who had taught himself architecture and apprenticed as a millwright. He built several wooden truss bridges in New England, including a bridge across Pisquataqua Bay that when it opened in 1794 had the longest self-supporting span in the world at 244 feet.

By 1804 ,Palmer had gained a reputation as a wooden bridge builder and upon being contacted by the bridge committee, submitted a plan that the committee approved.

Palmer brought along four or five skilled workmen and, according to a contemporary account: “They immediately evinced superior intelligence and adroitness in a business which was found to be a peculiar art, acquired by habits not promptly gained by even good workmen in other branches of framing in wood.”

$300,000 cost

Palmer’s bridge, which ended up costing the tremendous sum of nearly $300,000, featured a center span of 195 feet with each side span being 150 feet. Counting approaches and abutments, total length of the structure was 1300 feet. The bridge was 42 feet wide and rose 31 feet above the river surface, allowing only small ships to pass beneath.

The bridge was constructed entirely of about 800,000 board feet of white pine, except for the top layer of the double deck which was 2 1/2 inch thick pitch pine and meant to be replaced when badly worn, and the roof which was covered by 110,000 cedar shingles.

The original plan didn’t call for it, but committee president Richard Peters pushed for a roof and closed sides for the bridge.

Peters wrote: “The bridge if left uncovered, will most assuredly decay in ten or twelve years.”

He compares this to the Schaaffhausen covered bridge on the border between Germany and Switzerland which, “had been by its cover, effectually preserved from decay for thirty-eight years, and was perfectly sound, at the time that the French destroyed it.”

Palmer agreed completely and wrote to Peters: “[F]rom the experience that I have had in New England and Maryland that they will not last more than ten or twelve years for heavy carriages to pass over. Some have tried to paint in the joints, others turpentine and oil, but all to no great effect. It is sincerely my opinion that the Schuylkill Bridge will last thirty and perhaps forty years if well covered.”

Opened in 1805

As an aside, a Virginia builder supposedly once remarked that bridges were covered “for the same reason that our belles [wear] hoop skirts and crinolines: to protect the structural beauty that is seldom seen, but nevertheless appreciated.”

The ornate cover wasn’t yet in place when the Permanent Bridge was opened to traffic Jan. 1, 1805, although it was soon added at a cost of $8,000.

The cover “compelled ornament and some elegance of design, lest it should disgrace the environs of a great City,” so it was painted with a mixture of paint and stone and plaster dust to look like masonry, and was adorned with carved wooden figures representing Agriculture over the western portal and Commerce over the eastern.

Also, seven lightning rods, which had been invented by Ben Franklin barely 50 years before, adorned the ridge of the roof and were hoped to protect the structure from lightning strikes.

Charged toll

Tolls were charged for using the bridge and went toward discharging the debt incurred in building it. One-half cent was charged for each calf, swine or sheep, while “horned cattle” cost a penny, as did a person, and a rider on an animal was two cents.

Pleasure vehicles ranged from four cents for a one-horse, two-wheeled cart or sleigh, to 20 cents for a four-wheeled carriage pulled by four horses. Commercial vehicles were rated according to number of wheels, number of draft animals (2 oxen were considered the same as one horse), total tonnage (6 tons was the maximum allowed), and the type of load.

A wagon, cart, or sled that was empty or loaded with manure received the cheapest rate, a load of farm produce was a little more and everything else was the same higher rate.

For example, a one-horse, two-wheeled cart of manure cost 4 1/2 cents, while a 6-ton four-wheeler pulled by five or more animals cost $1.35.

Recreated everywhere

From this time on nearly every wooden bridge in the country was built as a covered bridge, so while there may have been more than one reason for covering a bridge, the primary one seems to have been to protect it from the elements so it would last three times as long.