For centuries, grain was threshed by beating the grain with flails, trampling it with horses or oxen, or by pulling stone or wooden rollers and sledges over it.

These endeavors succeeded in knocking the grain kernels from the heads, but left them all mixed up with the chaff, the straw and lots of dirt, leaving the task of separating the grain from the straw and chaff to a later operation called winnowing.

First, the larger hunks of straw and “stuff” were raked aside and the remaining grain, dirt, chaff and bits and pieces were swept into a pile. This mixture was shoveled into a large, shallow basket and tossed into the air. Hopefully, the dust, dirt, chaff and bits of straw were blown to one side by the wind and the heavier grain fell back into the basket.

In this country, winnowing usually was done on a barn floor in the current of air blowing through two open doors located opposite each other. When there was no wind, sheets or blankets were waved to create the air current.

Technology steps in

Obviously, winnowing was not only hard work, but was slow, tedious, and inefficient as well. There is evidence that winnowing machines, with rotary fans enclosed in boxes, were used in China as early as the Han Dynasty (206 BC – 221 AD). In the 1500s. Dutch East India Company merchants carried a lot of Chinese technology back from their trading expeditions in the Far East, and these machines were built and demonstrated in Holland.

A contemporary account of one such demonstration tells of a local dignitary who looked into the opening out of which the air was coming, and the force of the blast was enough to lift the wig off his head and carry it across the floor.

In 1710, James Meikle, a Scotch millwright, travelled to Holland where he saw winnowing machines of the Chinese design in use. When Meikle returned to Scotland, he built a hand-operated winnower with four canvas sails to provide the air. Meikle’s winnowing machine met with much prejudice, especially among the clergy, who labeled it the “Devil’s Wind” and thundered from their pulpits that the machine “impiously thwarted the will of Divine Providence, by raising wind by human art, instead of by soliciting it through prayer!”

Popularity grows

In spite of this opposition, winnowing machines caught on because of the big savings in time, labor and grain. James Meikle’s sons, George and Andrew, began building fanning mills in about 1768 that featured what was called a “double blast.” The uncleaned grain first passed through a “dressing” stage where the larger bits were blown away, after which the grain went through a “finishing” stage where a second fan blew away any remaining chaff and dirt.

In England, in 1761, William Evers patented a winnowing machine that combined a rotary fan with sieves. Later improvements included scroll-shaped fan housings for a more efficient wind blast, as well as a series of shaking, or vibrating, sieves, one above the other.

Winnowing machines were brought to America, where they are usually called fanning mills, before the Revolutionary War, but didn’t become popular until the large explosion in wheat production during the 1830s. Fanning mills usually consisted of a large wooden box, in the rounded end of which were four or six wooden paddles of about 24 inches in length attached to an axle that, through a series of gears, could be driven at high speed by a hand crank.

As the fan turned, air was taken in through adjustable openings at the sides of the fan, causing a blast of air to be blown across a series of two or three screens. These screens, of different sizes for different seeds, were mounted one above the other in a shoe assembly that was itself suspended inside the box on hinges.

An eccentric wheel on one end of the fan shaft drove a pitman arm that caused the shoe to shake back and forth as the hand crank was turned. Uncleaned grain was poured in a hopper at the top of the mill and, as the crank was turned, the grain fell and was shaken down through the smallest screen or sieve that would pass it.

The blast of air from the fan blew away all the chaff and dirt and when the grain reached a screen through which it couldn’t pass, it was shaken out a spout and into a container while the smaller weed seeds fell on through.

Improvements continue

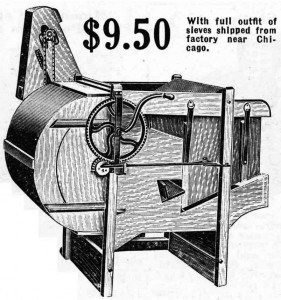

A 1916 catalog from the John M. Smyth Merchandise Co., offered the “Gem” fanning mill in two sizes. The “Gem” No. 1 cost $9.50, was 21 1/2 inches wide and had a capacity of 60 to 80 bushels per hour. $10.65 would buy a “Gem” No. 2 that could handle 70 to 100 bushels per hour with its 26 1/2 inch wide fan and sieves. A bagger and elevator attachment would add about $7 to the cost.

Furnished with each machine was a 3-gang wheat hurdle with a zinc top and wire middle and bottom sieves, a wheat grader, and a barley or bean sieve. Also included were barley or wheat screens, and a pair of blinds for the fan, along with a cheat, or chess board.

By the way, chessboard made me wonder, since I had never heard the term before, except in reference to the game. Webster’s Dictionary says chess, also known as cheat, is one of several brome grasses, usually considered a weed. I learn something new every day.

Use diminished

By the early 1900s, most fanning mills were used only for cleaning and grading seed, since modern threshing machines did the winnowing. The Smyth catalog claimed the outfits, as shipped, were able to clean and grade seed corn, by separating the small tip and butt end grains from the larger kernels in the center of the ear.

Optional accessories were listed for other purposes, such as separating oats from wheat, or separating mustard seed from oats. Screens for cleaning beans, peas, flax, millet, alfalfa, blue grass, timothy and clover seeds were available, as well. An 1894 ad for the Chatham fanning mill, sold in Ontario by Massey Mfg. Co., elaborated on the arrangement of the screens:

“The plan of placing the screens and riddles in the shoe cannot be surpassed. You can give them any pitch desired, and also put as many in at one time as you like, or as are required to clean the grain. You can use one riddle, or you can, by placing another under it, have a Two-ply, or you can put another under the second and have a Three-ply Gang. You can use one, two or three ply, as the condition of the grain requires.”

There was a fanning mill on the barn floor of our farm, with its faded red paint and gold stripes and curlicues a testament to the pride with which 19th century manufacturers decorated even such mundane objects. My father used the mill to clean wheat and timothy seed before planting, while we kids called the thing a “windmill” and would crank it up and stand in front of the outlet to cool off on hot days. Most fanning mills seen today are in museums or antique shops, but I’m sure there are some out there, tucked away in the corner of an old barn or granary.