Today the news is full of warnings about scams and swindles of all kinds, the bulk of which are associated with the internet or credit and debit cards.

As someone once said, “There’s nothing new under the sun,” especially the very human desire to “get something for nothing,” upon which many scams are based.

During the second half of the nineteenth century, there were scam artists and swindlers active in most every part of the American farming community.

With the prosperity brought to farmers by the higher prices for their crops brought about by the Civil War and the vast improvements in farm machinery and farm practices after the conflict, farmers had money to spend or to be cheated out of.

Lots of shady characters took advantage of the naive country bumpkins who were “ripe for plucking.”

Benjamin Franklin had experimented with lightning rods in the 1750s, but 200 years later lightning rod salesmen, known as “rodders” plagued farmers.

Rodders

A rodder would arrive at a farm in mid-afternoon while the farmer was in the field and regale the wife with stories of women and children killed by lightning.

When the farmer came into supper he was lobbied by both his wife and the salesman and often signed a contract. One farmer wrote of a neighbor who had signed a contract to have his house protected at a cost of “not more than $10.”

A gang of men then rodded the house, the barn, and all the outbuildings until “The farm bristles with lightning rods …like the back of a porcupine.”

The bill for all this was $335 — the “not more than $10” in the contract had been per rod, as was clearly stated in the fine print.

The Wisconsin State Grange Bulletin observed in 1885 that “if we had all the money that has been taken out of the pockets of Wisconsin farmers (by rodders), we could put a fine library in every Grange hall in the state.”

Inspectors

In the 1880s, Oregon steam engine owners were visited by bogus “State Boiler Inspectors,” who said a new law now required periodic safety inspections. After a more or less thorough inspection, the “inspector” collected a hefty fee and gave the engine owner a worthless certificate of safety.

Salesman

Then there were the Bible salesmen. They were well dressed and of a sober and prayerful mien and appeared right before mealtime.

They would be carrying a fancy leather-bound New Testament or Bible and when asked to sit and eat, as rural hospitality dictated, would agree only if they could pay for their meal.

After eating the shyster made his sales pitch, which was often successful, but if the farmer didn’t bite he was asked if he wouldn’t just sign a little receipt to prove the salesman had paid for his dinner. No harm in that, right?

The signed receipt, of course, later was given to the farmer’s bank as a legal note for a sum of money which the farmer owed.

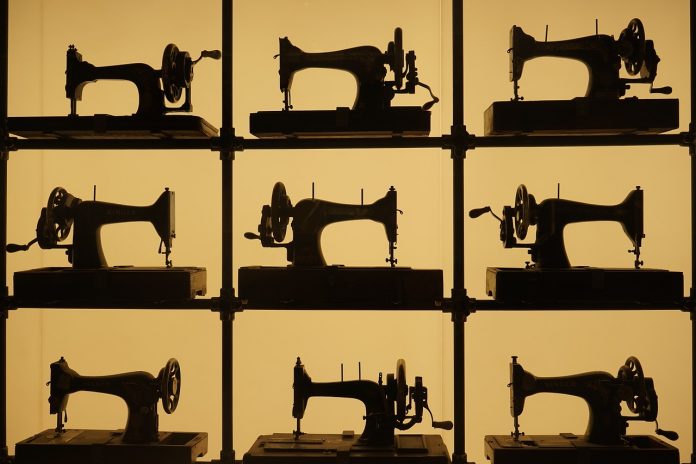

Then there were sewing machine salesmen! Farm women made lots of clothes by hand and most badly wanted a sewing machine, but they were expensive.

Imitations

However, the original Singer and Howe patents expired in the 1880s and a bunch of almost useless imitations flooded the market.

However, the original Singer and Howe patents expired in the 1880s and a bunch of almost useless imitations flooded the market.

These slickers proposed to give the farm wife a free machine if she sold five others for $50 each.

The agreement seemed to say that six machines would be shipped and if she sold five of them in six months she could keep the sixth. If the machines weren’t sold they would be taken back at no charge. Couldn’t lose, right?

But the sales agreement was cleverly designed so that after it was signed, the agent could cut away part of it leaving only a binding promissory note for $250, with no take-back provision.

This practice was called “note-shaving,” and was sometimes used by unscrupulous farm machinery salesmen as well.

A few fencing salesmen used the note-shaving scheme, while some used trick contracts. One of these swindlers offered to put up an eight-strand fence for an Illinois farmer at eight cents a foot. Too good to be true, right?

But the farmer happily signed and then after the fence was built found to his sorrow that the fine print read eight cents per foot per strand.

Oats

One of the most persistent scams of the time was for “Bohemian Hulless Oats.”

Salesmen visited a few of the more prosperous farmers in an area and offered them the chance to buy seed for Bohemian Hulless Oats, the finest grain yet discovered and only recently brought to the U.S.

These select farmers could raise a crop and then become rich selling the seed to their more unfortunate neighbors, who would be sure to be clamoring for some of the seed.

Of course, the salesman was charging $15 per bushel of seed, at a time when oats were selling on the market for around a quarter a bushel, but the slicker almost guaranteed that the farmer’s neighbors would beg to pay $15 for a bushel of seed of their own.

Of course, the seed the salesman sold was just an inferior grade of oats seed with nothing special at all about it. After making his killing in the one area, the salesman moved on and struck again in a new area.

The hulless oats racket started in Wisconsin and Northern Ohio, where one salesman was arrested, convicted of forgery and fraud and put away in the Columbus Penitentiary for seven years, and spread as far west as Oregon and northern California.

A USDA bulletin said, “It is an obvious fraud, that presupposes a crop can be sold year after year at the same price as the seed when the latter is 20 to 30 times the ordinary market price of the grain. This manifests a palpable lack of common sense.”

The bulletin didn’t add that it also manifested a palpable presence of greed among those that fell for the scam, just like today.