Folks today are used to innerspring mattresses, water beds, and even Sleep Number beds, where a couple can separately adjust each side to their own “ideal level of firmness, comfort and support.”

Consider then, bedsteads of our pioneer fore mothers and fathers, upon which, by most accounts, they slept quite comfortably and soundly.

In 1848, five families left Kokomo, Indiana, and traveled west by ox wagon to settle in what became Webster City, Iowa. One of the children who made the trip, 11-year-old Sarah Brewer, later collaborated with her daughter, Harriet Bonebright Closz, to publish a memoir in 1921, titled Reminisces of Newcastle, Iowa 1848.

Among many other aspects of pioneer life, Harriet discusses the sleeping arrangements and living conditions in the cramped cabins that were the early homes of most settlers.

Bedsteads

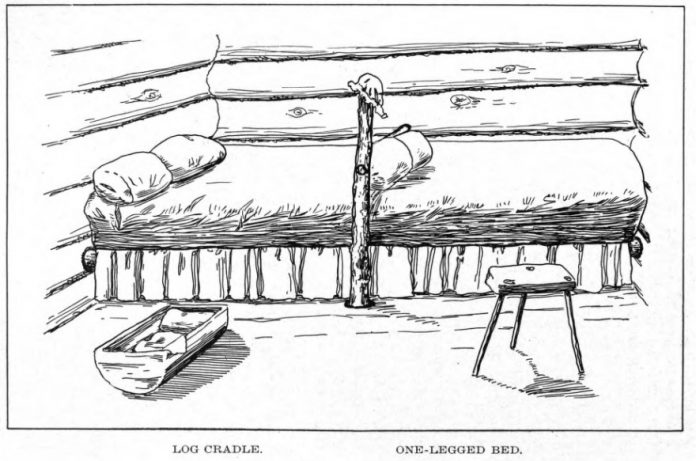

Harriet tells us, “The pioneer wall-bedstead had but one leg; and it was put in place by the cabin builders. Often two beds had but one leg — if the width of the cabin was 12 feet. I have seen two beds and several wall-bunks supported by one strong sapling leg.

“One end of the bed foot-rail and an end of the side-rail were fastened to the single bed leg and the other ends were fitted into holes augured and chiseled into the log walls. If bunks were to be installed, a high, stout timber leg was used.

“Holes were cut into it one above the other, two or three feet apart and the foot and side rails for each bunk were installed the same way.

“The ends of thin slats split from a log were stuck into the log-crevices in the side walls and the other ends rested on the side rails. Sometimes the slats slipped from the crevice and the bed occupants ended up on the floor. If cords were used instead of wood slats, a sapling was fastened horizontally along the wall and the rope crisscrossed from it to the side rail.

“Sometimes a linen blanket or quilt was fastened to the log wall and end and side-rails. This did away with the slipping slats, but the center sag was much greater than with the cord-woven support.

“A quilt tied to the rafters by ropes at each corner made a comfortable nest for a child and a low trundle-bed could be slid under the bedstead during the day and hauled out at night. The log cradle usually occupied the hearth.”

Harriet didn’t mention mattresses, as there were none, but most bed-steads had upon the slat or cord support what was called a bed-tick.

This was usually a wide flat sack sewed from linen or some other sturdy cloth, that was stuffed with straw, grass, leaves or corn husks and, as another commentator put it, “And here has been found as refreshing rest and as sweet dreams as ever came to royal palaces.”

Cold

Bonebright continues, “The now jocular expression: ‘two in a bed and three in the middle’ was no joke then. Bed assignments were made according to size — two grown-ups and one child at the head and two half-grown children at the foot of the bed; while two or three in the trundle bed was the rule, not the exception.

“Many a night visitors or travelers have slept soundly rolled in a quilt on the cabin floor and Indian transits slept before the fire wrapped in their blankets.

“During severe weather, all extra floor space was usually piled with game carcasses awaiting preparation for market, and not infrequently newly-dropped lambs or calves occupied the warm hearth and expressed their gratitude by plaintively bleating or calling ‘Maaa.’

“Dogs slept outside in the warm corners by the stone chimney, but snuck into the house at any opportunity and hid under the table or bed.”

Harriet doesn’t gloss over the more unsavory, to our modern eyes, aspects of cabin living.

She tells us: “In winter, the only ventilation in the cabin was through the wide fireplace; but with a sleeping contingent of from 10 to 20, the odor of bodily emanations and the varied but unclassified other smells taxed even its wide capacity.

“There were so many mice and they courted the company of the family so persistently that they made a playground of the benches, tables and beds at night. They scurried about the floor and cupboards during the day and, although they were slaughtered by the score, there was no noticeable diminution of numbers, for recruits filled the ranks before the victims could be thrown into the fire.

“Mosquitoes, like mice, were busy day and night and the humming of swarms of mosquitoes sounded like the approach of a coming storm. All day long the smudge-pot was industriously supplied with fuel and it was moved about the house as our working positions shifted.

“Everything about the cabin acquired a smoky look and feel.”

Bedbugs

Bedbugs apparently were another curse, as she attests. “The historian usually is discreetly silent about the courteously-named ‘crimson-rambler,’ but the bedbug is so cosmopolitan in his wandering, so active and so insatiable in his appetite that he compelled a painful and luridly wordy recognition from the pioneers.”

So, even as “discreetly silent” historians tell of “refreshing rest” and “sweet dreams” in those long-ago days, Bonebright paints a probably much more accurate picture.

I guess the early settlers were lucky that they had to work so hard to survive — they fell into bed so tired that they could sleep through even mice running over them and mosquitoes and bedbugs feeding on their blood.