William Tanner was Ferdinand Brader’s best friend. And now William Tanner was dead.

Brader had learned of his friend’s passing only days before, and borrowed money from Tanner’s friend, Anton Turajski, to make the trip from Canton to the funeral in Alliance. Brader promised to pay Turajski back upon his return, and knowing Brader as a man of few means, but a man of his word, Turajski believed him.

Related story: Bringing Brader back home

In fact, Turajski may have already heard rumors of a sum of money Brader had recently inherited, but had not yet received. Lending the little Swiss-born scenic artist money to get to the funeral seemed the least Turajski could do — and a fairly safe investment to boot.

Suffering from asthma, Brader’s artistic output had dwindled to around 30 drawings in 1895, from an average of more than 60 per year since arriving in America some 20 years before.

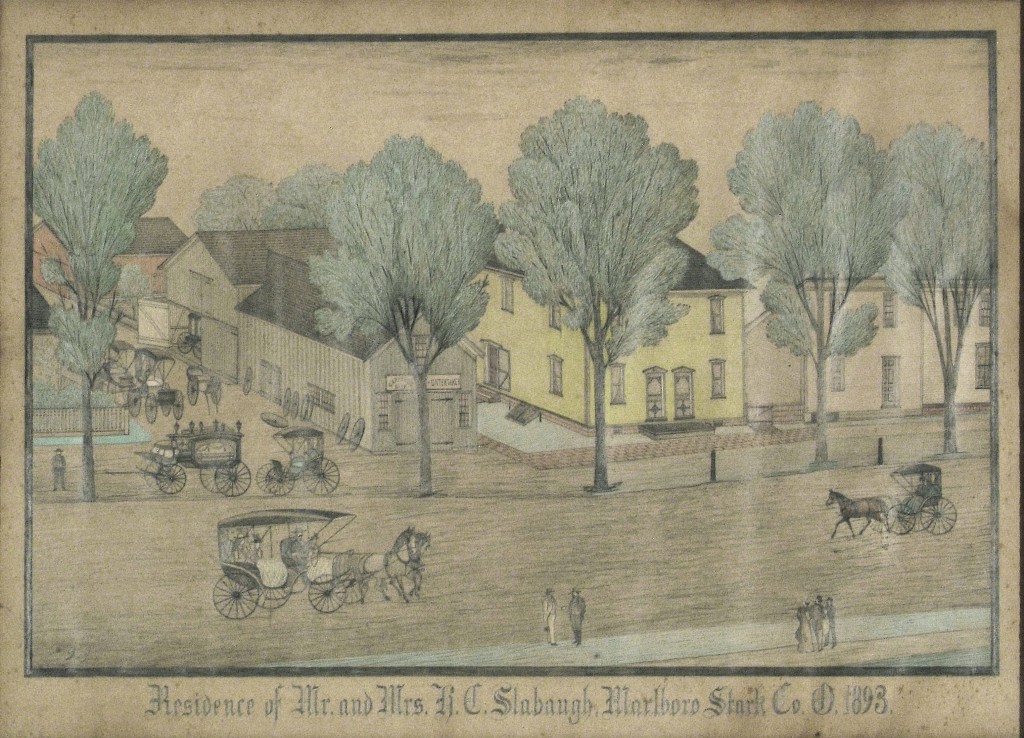

Now 62, Brader had cataloged a staggering 980 primitive, but highly detailed, graphite — and later, colored — pencil drawings chronicling the farms and factories of his adopted home country. Eking out a meager living traveling from farm to farm, he often created the massive 30-by-40-inch drawings for mere room and board.

But winters in northeastern Ohio could be brutal and Brader had spent the past four living in Stark and Portage county infirmaries, institutions commonly known as “the poor house.”

Curiously, as those closing days of 1895 found him returning home from a funeral, it was another death that took him back to his native Switzerland, where his greatest fortune awaited.

Brader begins

Ferdinand Brader came into Kathleen Wieschaus-Voss’ life as mysteriously as he seemingly disappeared from his own 100 years earlier. Wieschaus-Voss, a Canton-based art and antique appraiser, began seeing a number of Brader’s drawings showing up at estate sales in 1993, so she started to investigate. That initial curiosity soon became an all-out infatuation with Brader’s work.

“He was unusual not only in how he preserved and gave the names of the owners and locations of his drawings, but what was also unusual is that he was using the cheapest materials,” Wieschaus-Voss said.

“He was doing it to live, doing what he could do.”

Ferdinand Brader Exhibit Dec. 4, 2014 — March 15, 2015

Canton Museum of Art

1001 Market Ave. N.

Canton, OH 44702

330-453-7666

www.cantonart.org

William McKinley Presidential Library and Museum

800 McKinley Monument Drive NW

Canton, OH 44708

330-455-7043

www.mckinleymuseum.org

The Little Art Gallery at the North Canton Public Library

185 N. Main Street

North Canton, OH 44720

330-499-4712

www.ncantonlibrary.com/little-art-gallery

Wieschaus-Voss is guest curator of The Legacy of Ferdinand Brader, an upcoming exhibit of Brader drawings at the Canton Museum of Art in Canton, Ohio, Dec. 4 through March 15, 2015.

Collaborative exhibits will be staged at the McKinley Museum/Stark County Historical Society and at the Little Art Gallery in North Canton.

Born in Switzerland

Brader was born in 1833 in the village of Kaltbrunn, St. Gallen, Switzerland. And while his art would become synonymous with the farming industry in Ohio and Pennsylvania in the late 1800s, there is little indication that Brader or anyone in his family ever farmed.

“His family is from a tiny village of about 1,400,” said Wieschaus-Voss, who traveled to Kaltbrunn to research Brader.

Though probably as familiar with farming as any of his 19th century contemporaries, the Braders were bakers and tradesmen, Wieschaus-Voss said.

By the mid-1860s, Brader had married and had a son, Karl. He had also likely begun drawing.

There is not a lot known of his time in Switzerland, from 1864 ’til 1879, when his drawings start showing up in eastern Pennsylvania, Wieschaus-Voss said.

But Brader likely followed another brother to America, where his first drawings of farms appeared in 1879, in Berks County, Pennsylvania.

“If his wife and son were with him, they may have gone back,” Wieschaus-Voss said. There would have been some precedence for that, since he had a brother who came to America around 1863 and was recruited into the New York Cavalry during the Civil War, and his wife and daughter went back to Switzerland.

The answer may have been as simple, she suggested, as the reality of a new life in new country that did not quite meet expectations.

Vagabond artist

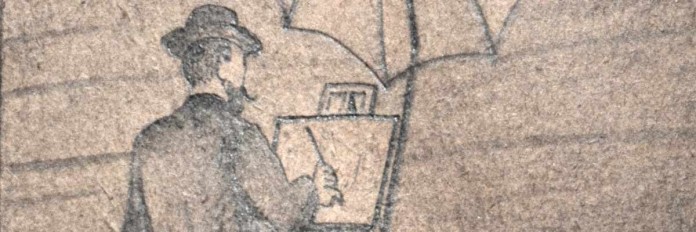

For his part, Brader decided to pack what belongings he needed, along with his pencils and reams of cheap cartridge paper, and hit the road.

He crossed into Ohio around 1884, drawing farms, factories, trains and towns in Columbiana, Tuscarawas, Portage, Medina, Wayne, Carroll, Mahoning, Summit and Stark counties. He would sometimes charge between $1 and $4 for a drawing, delivering his own “press releases” of sorts announcing his most recent or next project, which papers then printed as news. Brader was also known to display a recently completed drawing in a nearby shop window as a means of promoting his work.

By all accounts, though, the “little Swiss scenic artist,” as he was known, drew more for the love of it. Today, those sketches range in value from $5,000 to $30,000. At sales earlier this month, Braders sold for $11,400 and $12,000.

Brader self portrait

View

View

1892 portage county infirmary : no frame

A drawing by Ferdinand Brader of the Portage County Infirmary, commonly known as the “poor house,” where records indicate the itinerant artist spent a number of winters in the 1890s. View

View

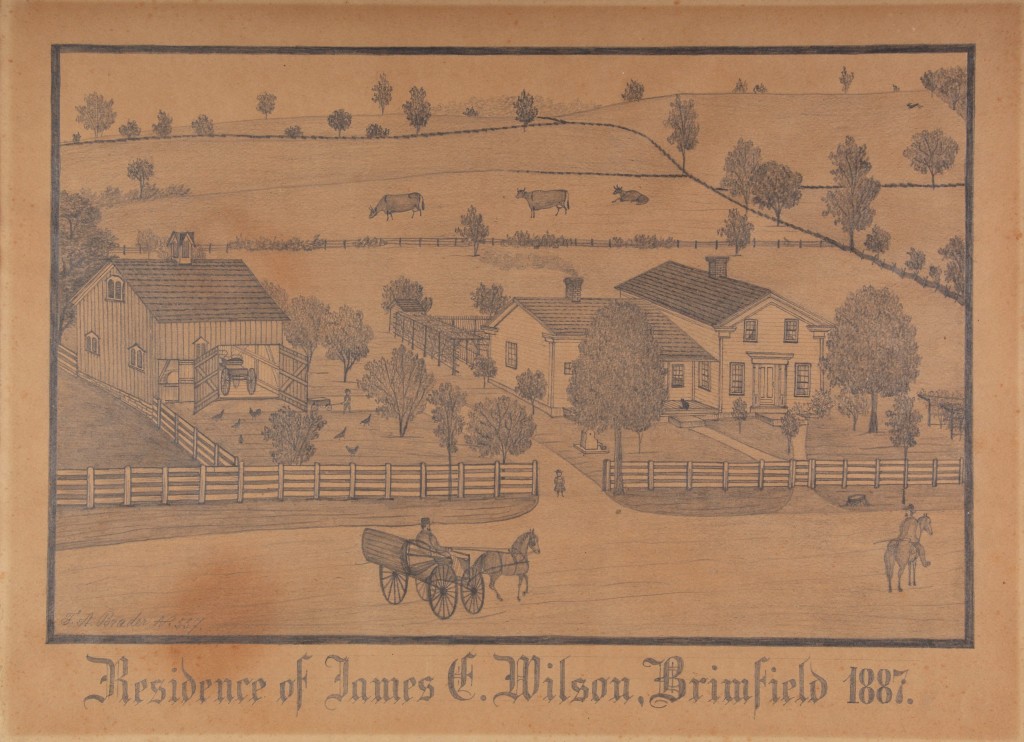

1887 #557 wilson

Swiss-born pencil artist Ferdinand Brader’s unique cataloging of his farm drawings in late 19th century Ohio and Pennsylvania, noting both the owner and location of each farm, helped preserve what was already becoming a disappearing agricultural culture.Into thin air

Anton Turajski was getting concerned. It had been weeks since he and Brader had returned home from Tanner’s funeral, and Brader had yet to pay him a visit, or pay him the money owed.

Turajski did know that Brader had received a money order and instead of returning to the infirmary, had gotten a room at a boarding house near the fairgrounds. Brader had also told several people that day that he was on his way to see Turajski and pay him.

Then Ferdinand Brader disappeared.

Over the next several weeks, the Canton Repository and Salem Daily News reported on the disappearance, noting that Swiss officials had searched for Brader for eight years and that he and his brother “were not on good terms and did not keep up a correspondence.”

Most assumed Brader had simply returned to Switzerland to collect his money. Turajski, however, had his doubts.

“Brader’s sudden disappearance is quite a mystery and it is thought that he was murdered and robbed or has wandered away,” the Daily News reported on Feb. 13, 1896. “Mr. Turajski said that Brader was afflicted with asthma and it might be possible that in his wanderings he may have been overcome and died in some out-of-the-way place. Mr. Turajski says he is certain that some misfortune has overcome Brader or he would have called and paid him.”

One month later, Brader wrote to the Stark County Infirmary, informing them that he had indeed arrived in Switzerland on Feb. 6. Records indicate, however, that he never collected his full inheritance.

In 1901, Brader was declared “lost and missing without a trace” by the Swiss government. The fortune was passed on to Karl, who was also declared “lost” by the government in 1911.

In 1919, the remainder of Ferdinand Brader’s monetary fortune was sent to the “Orphanage Office” in Kaltbrunn. His legacy, meanwhile, remained in a host of attics, barns, basements and milk houses across the Ohio and Pennsylvania countryside.

Special works

Wieschaus-Voss, who has organized three “Brader Day” exhibits — two at the Canton Museum of Art and one at the Canton offices of Kiko Auctioneers — said the stories behind the drawings are often as captivating as the drawings themselves.

The bank barn and one outbuilding in the Brader drawing of the Lutz farm on Paris Avenue in Louisville remains at Dan Grimminger’s family farm.

“In my case, the sketch was owned by my great-aunt and was hanging out in the milk house, hence the water damage,” said Grimminger, the great-great grandson of the Lutz family of Brader’s time. It wasn’t until the late ’60s that it was brought into the house.

“My great-aunt eventually hid it in the basement; she knew what she had, knew it was special.”

Related story: Bringing Brader back home

I enjoyed this very much and my wife had a drawing but it needed restored. We gave it to the Massillon Museum. I have an 8×10 copy that is beautiful. It is the Norman Horn Farm on Old Eshelman Road, now called Maplegrove.

Where are the sequential numbers located in Brader’s drawings?

Usually Lower Left corner along with his signature.

Sometimes lower right corner…

Usually Lower Left corner along with his signature.

Sometimes lower right corner…