CARROLLTON, Ohio — Ohio FFA Camp Muskingum Director Todd Davis’s connection to his place of employment is the stuff childhood memories are made of.

“My dad was camp director from 1968 to 1995, so I grew up here,” Davis said of the roughly 200-acre property, one of seven camps situated along the banks of 1,000-acre Leesville Lake in Carroll County. “My wife says I spend too much time at work.”

Considering the view from his “office,” it is kind of tough to blame Davis for that. And as Camp Muskingum enters its seventh decade, Davis hopes a pending $2.5 million building project will help keep it around for a good long while.

More than FFA

For the past 70 years, Camp Muskingum has served Ohio’s entire FFA membership, which now totals approximately 23,000 students. In that time though, the camp has been far from an exclusive club.

Davis has been camp director since 1996. From the days when his father, John, was camp director until now, the number of annual visitors has grown from around 2,000 a year to just shy of 12,000 in 2013, including 166 different groups, schools, and sports teams.

“We host a boatload of outside groups — church groups, band camps — those groups are a cash cow for us,” Davis said. “The vision of the (camp) board of directors has always been FFA first, as it should be. But when FFA groups are not using the camp, we can make money and develop programs to enhance camp and also help subsidize FFA campers.”

Those FFA subsidies, Davis said, amount to $50,000 to $60,000 a year, allowing an FFA student to attend a weeklong camp for $175. Overall, Davis said, the camp generates $1.2 million to $1.3 million a year, money that largely “comes in and goes back out” to continue operations and camp upkeep.

Many programs

In 1987, Camp Muskingum began administering Nature’s Classroom, a national residential outdoor education program serving elementary schools, middle schools and a variety of other groups interested in motivational learning and personal development.

The camp also offers groups live Underground Railroad program, where students take on the role of escaped slaves in 1850, trying to avoid fugitive slave hunters and make their way across the Ohio River, ably portrayed by Leesville Lake.

Likewise groups can take part in programs such as the camp’s Project Reach, which includes options like high ropes, low ropes, and paintball.

“It is about getting them out of their comfort zone and doing things they can’t do at home,” Davis said, noting how important coming to a camp like Muskingum can be to a suburban or inner-city student. “When you add in the leadership (training), it’s something they can’t get anywhere else.”

Shawn Neeley, an eighth-grade language arts teacher at Bell-Herron Middle School in Carrollton was recently at Camp Muskingum with a group of Carrollton Village Schools sixth-graders.

“It gives them an chance to get outside and play and get dirty,” Neeley said as he and his fellow teacher-campers ate lunch with the group on its first day at Muskingum. “They get clear of digital technology and their cell phones and they can understand stuff. Kids should do that and they don’t.”

Camp Muskingum’s Nature’s Classroom director Jody Rutten has worked at the camp for six years.

“I don’t think kids know how to play anymore — to get to play outside and learn,” Rutten said. “And I don’t think we give kids enough credit for what they know. It’s good to see them out of the classroom and learning.”

Community outreach

Since 1942, Camp Muskingum’s FFA camp has been the only experience of its kind in the state. First located in a barn across the lake from the camp’s current location, Ohio FFA camping activities were moved to Camp Muskingum, which at the time was a former youth occupational training site for President Franklin Roosevelt’s National Youth Administration program.

The property now includes 160 acres owned by the camp and another 45 acres that the camp leases from the Muskingum Watershed Conservancy District.

Recent upgrades have included improvements to dorms and the conference center, as well as leveraging oil and gas lease payments to turn the camp’s former community bathroom area into a modern lounge, complete with showers and space to sleep 24 people comfortably.

The camp’s most ambitious building project in recent years, however, came out of tragedy.

New direction

In 2011, a fire destroyed the camp’s nature center. USDA rural development insurance allowed for the rebuilding of a nature center area and new pavilion on the site of the original nature center, which the camp did as a short-term solution.

“But the board went back to our strategic plan to look at other things we could improve upon,” Davis said.

The result was the planned Muskingum Discovery Center, a $2.5 million, 7,500 square foot multi-purpose space including assembly and performance areas, classrooms for live animal education, all-weather recreational facilities, and a possible camp welcome center.

Plans also include “green” and environmentally aware technologies to increase efficiency and promote concepts of conservation and sustainability.

The camp recently received a $50,000 donation from Farm Credit Mid-America and has independently raised $300,000 toward the project. Plans are underway for a fall 2015 groundbreaking.

He added that camp officials are “really excited” about conversations with representatives from Hocking College and Stark State College’s environmental science program to potentially offer college courses at the camp.

Hidden jewel

From its inception, there has been a strong agricultural, water quality and conservation education curriculum at Camp Muskingum. But the primary focus, Davis said, has always about more than hands-on agricultural education.

“By coming to camp, you’re not going to learn the latest in no-till farming,” he said. “We are teaching things like what a watershed is and what water quality is, but we are also building young men and women into leaders and helping them to become the future of agriculture and the future of America.”

Davis said the wide range of socioeconomic backgrounds at camp also benefits both campers and staff.

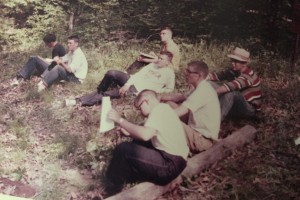

“I get to see a lot of good kids and this is a generation that gets a lot of bad press,” he said. “We can have 280 kids here —from districts like Akron, which is urban; Medina, which is suburban; and someplace like rural Tri-Rivers Career Center, most of which are in the ag mechanics program — and over two days, they find out there isn’t a lot different about each other. It goes back to personal development and leadership. It’s still very similar to what my dad was doing in 1968.”