I’ve always considered myself a “dog person,” but at the onset of spring each year, my thoughts turn to fuzzy felines as pussy willows begin to bloom. One of my favorite vernal traditions involves clipping a bouquet of willow branches and sticking them into a vase on my kitchen counter. In this way, I gain a front row seat to the unique flowers as they emerge and mature.

The American pussy willow (Salix discolor) is a small species of willow native to North America. Also referred to as the American glaucous willow, they are often located throughout damp habitats. Maxing out at around 20 feet in height, the multi-trunked plant is often as tall as it is wide, with an overzealous root system.

Flowers

Its name is a nod to the velvety silver “catkins” (the Dutch word for kitten, katteken) that appear along the branches as the weather begins to warm. Pussy willows are dioecious, meaning that some plants are male, and others are female. But it is only the male plants that produce the fuzzy flowers for which they are named. Female plants produce small, greenish flowers that resemble spiky caterpillars and provide a vessel in which the seeds will develop.

Catkins emerge from shiny brown bud scales along the branches. As they push their way out into the world, the fuzzy silver structures attain lengths between 1-2 inches and resemble tiny cat paws which are soft to the touch. The “fur” which covers the reproductive structures beneath acts as insulation to protect them from the cold. Although they look like a single unit, each catkin is composed of many individual flowers. Pussy willow catkins do not develop petals, nor do they have a fragrance. As the flowers mature, they send out oodles of yellow stamens, each with a tiny clump of pollen at the tip.

The giving tree

Pussy willow flowers are unique, as they rely on both the wind and a host of insects to achieve pollination. Their lightweight pollen grains are easily lofted into the air on breezy days, where they are carried to nearby trees for cross-pollination. A host of early insect pollinators also take advantage of the pollen-rich structures, including mason bees, mining bees, honeybees and several early butterflies such as mourning cloaks and anglewings.

Willows, in general, provide a smorgasbord for many species of wildlife. Squirrels relish the buds, and deer, muskrats and other mammals feast on the leaves and branches. Dozens of butterfly and moth species depend upon the willow as their larval host plant, the caterpillars feasting on the foliage. Hummingbirds have been known to weave the soft “fur” from the catkins into their nests. So important are willows that the National Wildlife Federation lists them as a native keystone species for the food web.

One species particularly dependent upon willows is the pinecone willow gall midge. This tiny gall wasp is responsible for creating the small brown structures that adorn the tips of many willow branches. A gall is an abnormal growth found on a plant, caused by the eating or egg-laying activity of an insect. When a gall wasp deposits an egg, it injects hormones that aid in the creation of the gall structure by altering the leaf’s typical growth pattern. Slowly, the affected area begins to grow, aberrantly, around the egg, getting larger as the plant matures. The size and shape of the gall is indicative of the species that created it. It just so happens that the galls found at the tips of willow branches grow in such a way as to resemble pinecones. Inside of each gall, a tiny larva overwinters and emerges in the spring as a winged adult. These insects do no harm to the plant and often provide food for birds which peck their way into the structures during the winter for the fatty grubs within.

Medicinal properties

Willow has been utilized for thousands of years as an herbal remedy. The bark, which contains a compound known as salicin (similar to aspirin), elicits anti-inflammatory properties. Native Americans were known to have chewed on willow bark as a natural pain reliever. Throughout history, people have relied on willows to aid in the relief of back pain, headaches, osteoarthritis and muscle aches. Even today, willow can be found in many supplements on store shelves, although there is limited scientific evidence to support its effectiveness.

As the willow twigs in my vase progress, the flowers bloom and fade and the leaves begin to emerge. Small rootlets creep out from the end of the twigs. Unlike many household bouquets that are eventually discarded as they fade, willows flourish. Take them to a damp location and simply poke them into the ground, and you will be happy to find healthy plants thriving in the future, displaying their fuzzy catkins which herald the arrival of spring.

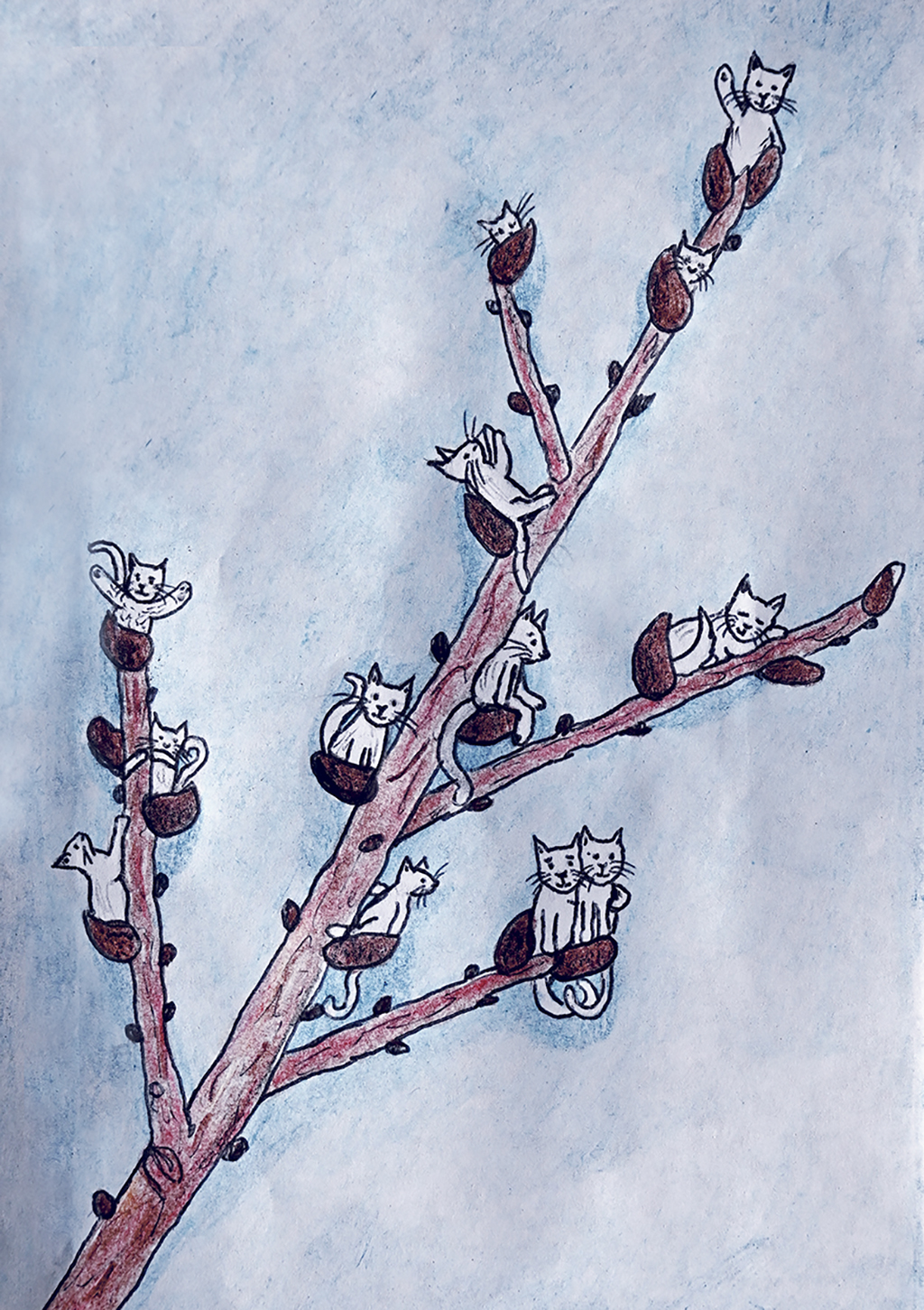

In her poem” Legend of the Pussy Willow,” author Dot McGinnis recounts

the story of how the pussy willow earned its name:

A Polish legend tells the tale,

of tiny kittens, oh so frail.

Along the river’s edge they chased.

With butterflies, they played and raced.

They came too close to the river’s side,

and thus, fell in. Their mother cried.

What could she do but weep and moan?

Her babies’ fates were yet unknown.

The willows, by the river, knew

just what it was that they must do.

They swept their graceful branches down

Into the waters, all around.

To reach the kittens was their goal;

A rescue mission, heart and soul.

The kittens grasped the branches tight.

The willows saved them from their plight.

Each springtime since, the story goes,

Willow branches now wear clothes.

Tiny fur-like buds are sprung

where little kittens had once clung.

And that’s the legend, so they claim,

How Pussy Willows got their name!

Great article! Informative and beautifully written!

Great piece on pussy willows! When they are in full yellow fuzzy bloom on a mild sunny day they can have a mild fragrance To my nose they smell pleasantly sweet and like springtime!