During a 1916 Preparedness Day parade in San Francisco, someone exploded a bomb. A prominent Socialist labor leader named Tom Mooney was tried, convicted and sentenced to death (later changed to life imprisonment) for the crime in a questionable trial.

The week of July 4, 1919, workers around the country struck to protest Mooney’s imprisonment. The coal miners around Belleville, Illinois, joined the strike and, in accordance with the union contract, were docked next payday for the wildcat protest.

Strike

The coal miners had many additional grievances and again walked out. The strike quickly spread in spite of the United Mine Workers union’s efforts to stop it.

The strike dragged on into winter and coal became scarce, this at a time when most folks heated with coal and factories relied on steam for power and light.

The shortage of coal became acute, with folks huddling under blankets to keep warm in their homes, factories shutting down, and some towns without power.

The federal government curtailed the use of coal for light and power and diverted the fuel thus saved to domestic uses.

A 1919 U.S. Government survey reported, “In not a few places where temperatures were below zero, a fuel famine existed. In the emergencies, much volunteer coal mining was attempted. College and university students went into the surface mines in Kansas.

“In Montana, on the other hand, it was reported that federal troops were used to drive miners to work. The secretary of war announced that such an action was inconceivable, but it’s unclear what actually occurred.

“In North Dakota, Gov. Frazier took over the mines under martial law, and the union miners returned to work under the auspices of the state government.”

A December 1919 story in Tractor World magazine tells of the problems and how some resourceful business leaders managed to stretch their government allotted coal rations.

It points out that the Midwest was particularly hard hit because industries there had long relied on continuous coal supplies and hadn’t found it necessary to accumulate large coal reserves.

The 1919 article continues, “Most of the companies manufacturing tractors and agricultural implements felt the fuel reduction keenly, and not a few of them utilized tractors as power plants and were able to continue, some of them producing light from temporary generators.

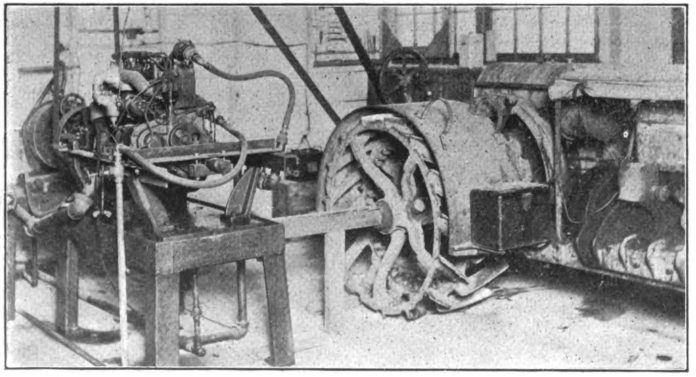

“Each plant was an individual problem that the executives studied and dealt with according to their resources. The Avery Co. at Peoria, Illinois, by installing tractors, was able to develop 450 horsepower for its different shops. One concern is credited with using no less than 30 tractors in its works and many of the companies used smaller numbers. Where the power needs were small a single tractor was adequate for power, as at the Lansing, Michigan, plant of the Briscoe Devices Co. where a tractor was placed in the powerhouse and drove the plant’s machinery as well as an electric generator.

“Truck and tractor engines were set up whenever possible and trucks were often driven into the shops with pulleys rigged on the rear axle or the uncoupled main drive shaft and belted to the factory overhead line shafts. Sometimes the engines needed auxiliary cooling apparatus.”

The article points out that, while the makeshift power was more expensive, it did make possible operation so far as light and power was concerned and reduced the need for coal to that used for heating alone.

Although not related to the coal shortage, an October 1919 story told of several “unusual” uses for tractors.

Tractor uses

Here are a couple of them that were obviously provided by the Cleveland Tractor Co.:

“In the town of White Deer, Texas, a Cletrac is used for generating electricity for lighting the town. [In 1920, White Deer had a population of around 200 people, so it wasn’t a huge task].

– “The tractor is geared to 800 RPM and the generator 1800. The machine is on the job from 7:30 to 11:30 p.m., and during the day it is used for operating a grain elevator in the town. Another instance of the use of this type of tractor for generating electric power is reported at Elgin, Illinois, where it has been operating a 25-horsepower generator for a number of weeks, averaging 12 to 14 hours a day.”

– In another example, we read, “The three-story building of the Lincoln Collar factory at Lincoln, Illinois, was recently destroyed by fire, but some of the walls were left standing and were a menace to street traffic.

“The fire department tried to pull down the walls with a large truck but was unsuccessful. It next tried dynamite but after three charges the wall would not budge. The fire chief then decided to try a tractor and chose the Cletrac, which is sold in Lincoln by Wilson & Coddington. The walls were finally leveled, after a cable was broken six times and a heavier one twice.

“A still heavier cable was used and the tractor could than make its power effective.”

During the teens and ’20s, a time when the new-fangled contraptions were looked at skeptically by most American farmers, tractor power was heavily promoted by power and farm publications such as Tractor World, a monthly published in Pawtucket, Rhode Island.

Any story about an unusual use for a tractor was eagerly pounced upon by these magazines and published in the hopes of converting a few more horse farmers to tractor power.