OK, so antlions don’t make any noise, at least nothing audible to our ears. But they are one of the most fascinating and unique insects that I’ve ever had the chance to get to know.

It’s been a few years since I’ve noticed them around, so when I saw a group of small, conical pits in the sandy soil beneath my common milkweed plants a few days ago, I just knew they had to be the star of this week’s article.

Antlions

Antlions are unique insects belonging to the order Neuroptera, a group known as net-winged insects that also include lacewings and mantisflies. With a life cycle referred to as complete metamorphosis, the antlion passes through four stages: egg, larvae, pupae and adult. Yet, it is the larvae stage from which the insect derives its ferocious name.

The eggs of the antlion are laid in sandy, fine-grained soil, usually in a location sheltered from rain. From these, the larvae emerge, every bit as scary as their name implies. They have a plump, robust abdomen, a thorax sporting three pairs of legs and a flattened head. Emerging from the front of this structure are two formidable sickle-shaped jaws covered with sharp protuberances. These specialized mouthparts contain an enclosed groove, a canal, that is used to transport and inject venom into their prey. Forward-pointing bristles on the antlion’s body help to anchor it in place, giving it traction when subduing a food item that is larger or stronger than itself.

Setting a trap

Yet, the most interesting aspect of the antlion is the unique way in which it goes about procuring a meal. Selecting a site in a sheltered location where the soil is fine and/or sandy, the antlion begins its excavation. Traveling backward, the only direction in which it is capable, the insect uses its abdomen as a plow. With its front legs, it repositions the loosened soil atop its head, and with a powerful flick, expels it from the area. Round and down the larva spirals, tightening the circumference of the circle with every pass until finally, it reaches the very bottom of the pit. Here, careful not to disturb the fine grains making up the walls of the structure, it buries itself, leaving its powerful mandibles exposed and wide open above the substrate.

Now it waits until an unsuspecting ant (or other small insect) blunders into the pit. In an effort to exit, the ant tries to climb the walls which collapse beneath it. All the while, the antlion uses its head to throw sand upward, hindering the insect’s progress but, more importantly, causing the walls of the structure to collapse, propelling the prey downward, directly into its waiting jaws. Using its venom, it quickly subdues the prey, slowly pulling it down and out of view. After a few hours, the dehydrated body of the meal is flicked high out of the pit where it joins other spent corpses around the edge. Soon, the antlion gets to work, reconstructing its amazing architectural creation, one of the most unique in all of nature.

If an antlion isn’t having much luck catching prey in its current location, it will relocate. As it moves in a backward motion in its search for a new site, it leaves silly, spiraling tracks in the soil resembling doodles on a piece of paper. Thus, an antlion is often referred to as a doodlebug.

Depending upon how much nourishment it can obtain, the antlion may have to remain in its larval form for up to three years.

Transformation

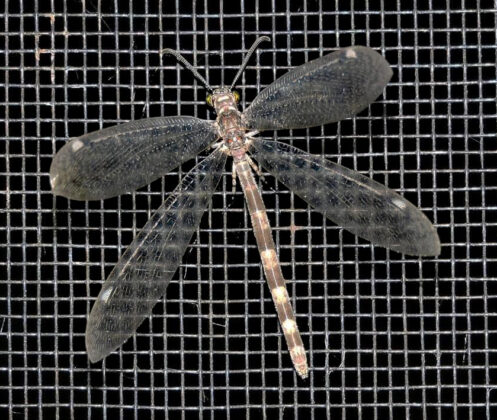

Finally, it forms a cocoon beneath the soil and after a few months, emerges as a much-transformed adult. What was once a spiny, ferocious larva, is now a beautiful, winged insect bearing a resemblance to a dragonfly. It has two pairs of narrow, translucent wings that are multi-veined and prominent clubbed antennae. Unlike dragonflies and damselflies, adult antlions are nocturnal, flying during the night, searching for a mate and often appearing at porch lights. As adults, they have traded in the necessity for live prey for a vegetarian menu of flower nectar and pollen. The adults live but a few weeks, long enough to mate and deposit their eggs into loose, sandy soil in a sheltered location.

One summer during my tenure at the Geauga Park District, I decided to keep a small colony of antlions on my desk, located in the basement of the nature center. In a wide-open vessel, containing fine, sandy soil, a group of five doodlebugs set up housekeeping in my cubicle. My goal was to rear them until they turned into beautiful winged adults, as well as use them in programming.

It wasn’t long before word spread throughout the staff that I had something super cool on my desk. Daily, a steady stream of employees would visit our office. Some poked their head inside the door, entering timidly with a single ant between their fingers, while others swung the door open wide, proudly displaying a container full of ants upon entry. The amusement of dropping an ant into a pit and seeing it slowly dragged down into the center where it finally disappeared from view was a novelty that never seemed to wane. I’m not sure if upper management (also in the building) appreciated the distraction, but I chalked it up to a learning opportunity that anyone working for a park district should definitely experience. After all, my antlions never went hungry and I made a lot of new friends.

For an entertaining, close-up look at antlion larvae in action, check out the Smithsonian Channel’s video at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q2K3v29zeOM.

I raised a group of Antlions and I had the same experience as you and made new friends also.

I wasn’t expecting a round cocoon. It was a lot of fun and a great learning experience.

What a fascinating article! When I saw the photo of the Antlion,I was reluctant to read about it.But what I learned made up for it.Thank you for a fascinating article!

I am always excited learning about insects I have never seen before-from the Tomato Horn Worm to the Antlion,giving me even more respect for lowly insects.

Thank you very much.