The U.S. entered the 19th century as a small agrarian nation heavily dependent upon others for essential manufactured products. By the end of the century, it had become a rich and powerful country with a diversified economy, well on the way to unquestioned leadership among the world’s industrial states.

In the middle of the 19th century, there were more inventions in America than in England and Western Europe. The patents they obtained in Washington soared in numbers, averaging 646 per annum in the 1840s. The inventors were the likes of Eli Whitney (cotton gin), Robert Fulton (steamboat), Cyrus McCormick (reaper), Samuel Colt (guns), John Ericsson (naval engineering), Charles Goodyear (rubber), Samuel F.B. Morse (telegraph) and Elias Howe (sewing machine).

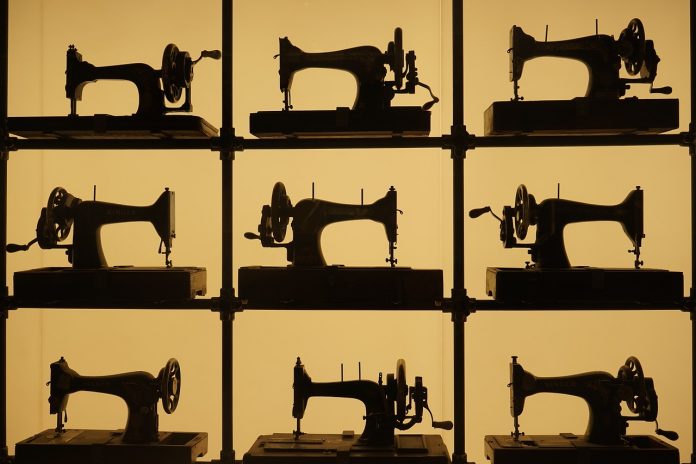

While the invention of the sewing machine represented the vitality of American inventiveness and “Yankee” ingenuity, the spectacular results of the sewing machine industry symbolized the evolution of the American mercantile economy into the age of industrial capitalism.

Howe’s invention of the sewing machine in 1846 can be given an Oscar for the great event in American history, but in truth the actual circumstances surrounding the machine’s origins and development of the industry involves many individuals whose claims to fame are as legitimate as Howe’s.

By the 1830s, America had passed beyond the age of self-sufficient household economy to a point where households depended upon specialized producers for many of their daily needs. As early as 1831, the first ready-to-wear clothing factory appeared in the United States. All the work in the operation was done by hand.

Necessity

Soon other similar factories appeared; the American market was ready for a sewing machine. The first machine of record was by an Englishman, Thomas Saint. Designed to sew leather, it never got off the drawing board.

In the 1820s, Barthelmy Thimonnier produced a machine in France that worked but fell victim to irate tailors who believed the machine threatened their livelihood. It was destroyed during the upheaval of the 1848 Revolution in France.

During that same period, an American named Walter Hunt developed a machine for “sewing, stitching, and seaming cloth” in New York City. Like the French model, it fell prey to social conditions and hostile beliefs that seamstresses would be thrown out of work. Hunt did not seek a patent and abandoned his project in 1838.

Long quest begins

That same year, Elias Howe, who would win a gold medal at the Paris Exhibition of 1867 for his invention, started on his long quest to construct a machine that could sew. Elias was born in Spencer, Massachusetts, on July 9, 1819. His early years were spent on his father’s farm.

In 1835 at Lowell, Massachusetts, he employed himself as an apprentice to a builder of precision instruments. While working in his shop, he overheard a conversation between his boss and a customer to the effect that a fortune awaited the man who could develop a practical sewing machine. The pursuit of the goal became an obsession with the poverty-stricken Howe.

After years of experimentation and failure, he obtained a patent in 1846. The Howe sewing machine solved the riddles of the machine and introduced the shuttle and the pointed-eye needle. After securing his patent, Howe made an unsuccessful trip to England to market his invention.

Upon returning home in 1849, he discovered that it had a ready market, but many competitors were already crowding the market with machines that infringed upon his patent. After much litigation, his patent rights were established, and he realized something over $2,000,000 for his invention.

Singer’s mass marketing. The most important of these competitors was Isaac Singer, who in 1850 began to market the first really practical sewing machine in the United States. Singer and his forward-thinking company not only perfected the machine but also were the first to develop mass marketing techniques for its sale. By 1860, the company was producing 111,000 machines annually. They were sold by an aggressive force of some 3,000 salesmen for both domestic and commercial use.

With professional seamstresses barely able to eke out a living with 18 hours of slow laborious hand-stitching a day, the machine proved a vast success in the clothing industry. The garment districts of various cities were soon using the machine extensively, and by the Civil War (1861-1865) thousands of sewing machines were producing shirts, collars, coats and trousers for the Union Army.

Industry takes off

The value of American ready-made clothing production increased from 40 million dollars in 1850 to 70 million dollars in 1870. Since the machine proved capable of sewing through leather, it was gradually adapted to all the sewing phases of shoe production. By the 1880 mechanization and labor of producing a pair of shoes, which had been 75 cents, was reduced to about three cents per pair. By 1895, the number of shoes produced by machine had reached 125,000,000.

Similarly, the machine was used for the production of saddlery and harness. The Civil War brought final and dramatic proof of the machine’s capabilities and importance to the economy. At the beginning of the conflict, soldier’s uniforms were imported to meet the demand, but by 1863 a mechanized domestic industry was able to clothe the entire army.

In similar fashion, the boot and shoe industry rapidly expanded to meet the wartime emergency. It was somewhat different in the Confederate states. The sewing machine, its production, its sales and the industries it spawned had clearly become big business by the end of the 19th century.

The sewing machine was tied to the growth of mass advertising and new communication methods, transportation, adjustment of labor wages and conditions and the standard of living. The liberation of women from hours of tedious sewing meant they now had leisure time to become connected to social, economic and political causes in the community.

Furthermore, the sewing machine represented the emergence of an industry dominated by the type of specialized entrepreneurs who concentrated on production of a single item and the phasing out of the merchant with diversified interests.

With this transition, America entered the age of industrial capitalism. Howe’s sewing machine invention, like other mid-19th century inventions, was of far greater benefit to a subsequent generation than to the one that produced it. That’s your history!